In 2008, Henry Cooper Toasted

For His Gentleness, Sense Of Fun

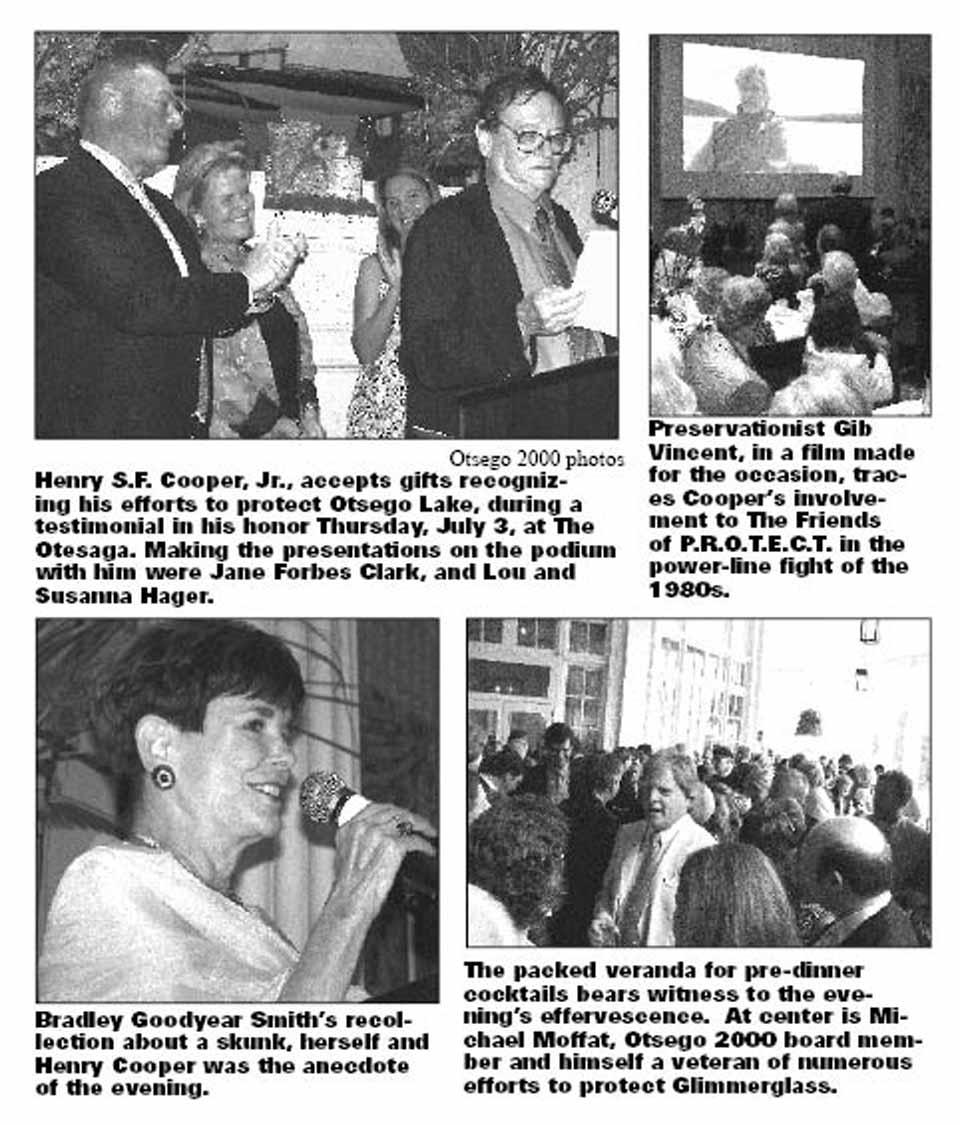

Editor’s Note: This is reprinted from The Freeman’s Journal edition of July 11, 2008, after Henry S.F. Cooper Jr., who passed away early today, was celebrated at a testimonial in his honor at The Otesaga, attended by 220 of his many admirers.

By JIM KEVLIN • from The Freeman's Journal

COOPERSTOWN – Everybody agreed Bradley Goodyear Smith’s story best captured Henry S.F. Cooper, Jr.’s gentle personality.

On her way to a party, her car hit a skunk and she ended up smelling like one.

At the party, everyone stayed away. Except Henry Cooper, who insisted on repeatedly twirling her around the dance floor.

On her way home, she realized the aroma was so strong Henry must have ended up smelling like a skunk, too.

When the guest of honor took the podium to address 220 well-wishers at Otsego 2000’s Thursday, July 3, testimonial in his honor, he wouldn’t let Bradley Smith get away with making him seem like a nice guy.

“What makes you think I don’t like to smell like a skunk?” he asked.

There were more serious stories, but the skunk one captured the evening’s light-heartedness.

You have reached your limit of 3 free articles

To Continue Reading

Our hard-copy and online publications cover the news of Otsego County by putting the community back into the newspaper. We are funded entirely by advertising and subscriptions. With your support, we continue to offer local, independent reporting that is not influenced by commercial or political ties.