MISSION in TOKYO BAY

MacArthur Wanted Surrender –

And To Hear Army-Navy Game

By LIBBY CUDMORE • Special to www.AllOTSEGO.com

COOPERSTOWN – At the end of World War II, Sgt. Wallace Low remembers a particular assignment while stationed with his communications unit in Yokohama Bay to handle communications during the Japanese surrender.

“General (Douglas) MacArthur wanted to listen to the Army-Navy football game,” he said. “Our orders were to set up the receivers so that he could get the entire game – in Alaska, San Francisco, Hawaii and Australia. If one started to fade, we switched over to the other!”

MacArthur was able to listen to the whole game, and afterwards, went by to meet the men who made it possible. “He shook all our hands and thanked us personally,” said Low. “And even though he did not drink, he served us all whiskey!”

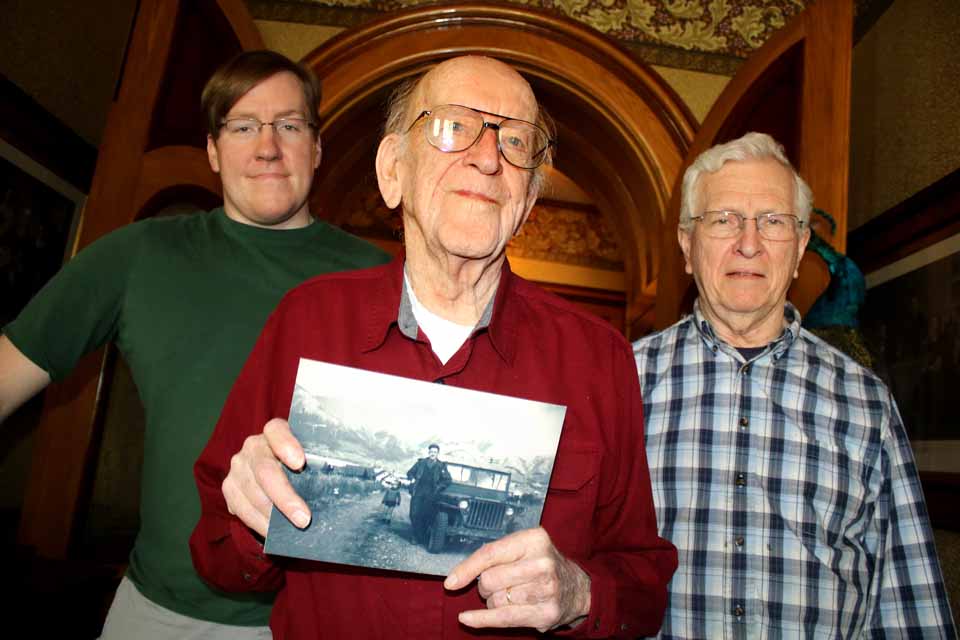

Low, 94, the father of Janet Rigby and a frequent visitor to Cooperstown from his home in Boonville, served in the Pacific Theater, from his 1942 enlistment until January 1946.

He should feel at home in the Rigby home at Elm and Delaware: his son-in-law, Bill, was a Vietnam-era Cee-Bee 1969-75; Grandson Will, now studying computers at SUNY Cobleskill, served for four years aboard the USS Ronald Reagan.

“I enlisted in the Reserve Corps right after my birthday,” said the family’s patriarch. Age 18, “I was a private, but I could go to school.”

He attended RPI, and on weekends would be sent to the Army Quartermaster Depot in Scotia.

“They wanted continuous operations, so they would send a bus to the school to pick us up at 10:30 at night,” he said. “I was assigned to the Engineering Storage, they paid us $15 a day and at 2 a.m. came around with free coffee and donuts.”

Soon, Uncle Sam wanted more. Low was sent to Army Specialist Training and trained to be a radio operator. “They called us ‘Dit Da Artists’,” he said. “I could type 60 words a minute.”

Messages would come in, he explained, and go through the code machines, coming out in five-letter increments. Radio operators like himself would type Morse code to send out the messages.

He was sent first to Finschhafen, New Guinea, in November 1943, which had just been successfully defended by Australian and American forces against the Japanese. “We were there for Christmas,” he said. “It was 95 degrees, and we were all running around in our shorts.”

Many of the men were homesick, and he got a choir together as part of a Christmas service. Bing Crosby’s “I’ll Be Home For Christmas” had just come out, “so we learned that,” he said. “It was the first time many people had heard it, and I’d say 80 percent of the guys had their hankies out when we sang it.”

In April 1945, his unit was sent to close down radio operations at the air strip on Biak, seized by Allies following a bloody battle in 1944. “We had been using the airfield, but they wanted to close down the radio operations, and sent us,” he said. “We were there five or six days operating the system to let everyone know there wouldn’t be anyone there.”

They got one important message while stationed there: that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had died April 12 and Harry S. Truman had succeeded him.

And that July, he noticed that a lot of communications were coming in from San Francisco. “We knew something was up,” he said.

An “eyes only” message for Gen. Robert Eichelberger came through in August, and the radio operators were asked to leave the room. “The colonel came in and decoded the message, then took it to General Eichelberger personally,” he said. “Japan had surrendered.”

Forty radio operators, including Low, were summoned to Yokohama Bay, setting up their operations in a former maternity hospital, one of the last buildings left standing around the port.

“There was a big blank wall, and George Petty’s nephew Kent was in our company,” he said. An illustrator, Petty was known for his pinup girls – dubbed “Petty Girls” – in Esquire Magazine. “So his nephew put up this big beautiful nude, but when the Colonel saw it, he had to paint on a bra and panties.”

They hired a local man to help build the base, and he brought his wife and two little girls, 7 and 4, to live there during construction. “They were Christians, but they had never had Christmas,” he said. “So all of us wrote home and asked them to send gifts.

“We gave them a great Christmas party and taught them ‘Silent Night’ in English. They tried to teach us in Japanese, but I don’t think we learned.”

Though the war was over, he was declared necessary personnel, and was tasked with finding additional places to put transmitters. With a pass signed by General MacArthur in hand, he toured Japan for five days, looking for places to put towers.

One place he visited was Atami, a village that had been taken over by the Nazi forces. “The Japanese wanted German optical, but the Germans didn’t want to give out their secrets, so they moved their people there.”

On the road, he was greeted by a blonde haired boy, who pointed them to a Bavarian-style inn. “Money meant nothing,” he said. “We paid for our room with canned meat, veggies, beans and eggs. And they made us dinner!”

He was sent home in January 1946 and returned to school at RPI. He met his wife, Eileen, at a dance at Russell Sage shortly after his return, and they had four daughters, Linda, Janet, Chris and Victoria.

An engineer, he was involved in construction of several factories, including Revere Copper and Brass, and ran the Christmas Tree Campground in Boonville.