Travels with ‘Cesca by Francesca Zambello

Greetings from Mississippi and Yucatán

For regular readers, you may recall that I previously shared the embarrassing fact that my family claims I know very little about the American South. My wife, Faith, who grew up in Statesboro, Georgia, has taken it on as a personal mission to more fully educate me about our nation’s history, especially that of the South.

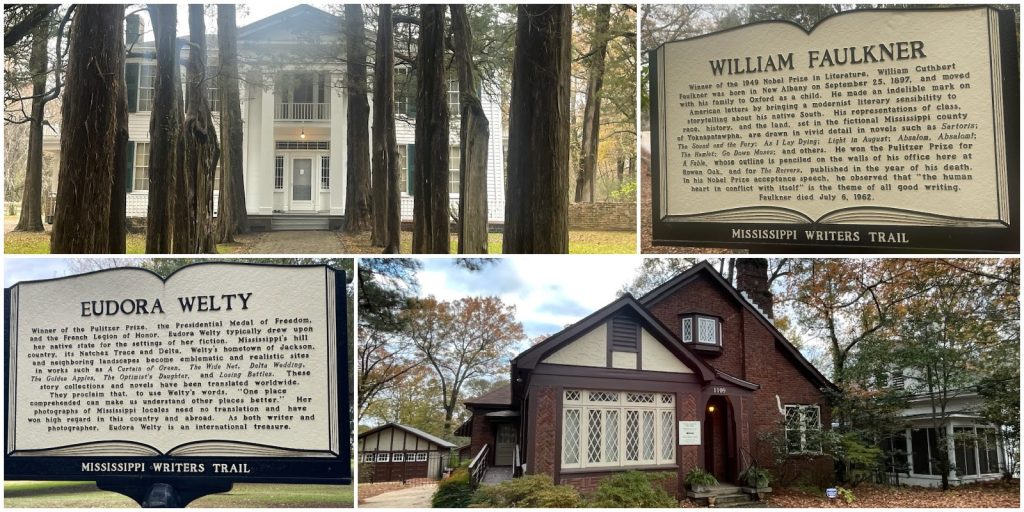

To that end, we have thus far visited Virginia, Georgia, Alabama, and Louisiana—with future trips to West Virginia and Tennessee on our bucket list. Recently, we traveled to Mississippi. Before we left, all I knew about Mississippi came from the writings of Eudora Welty and William Faulkner, so I was delighted to have my knowledge expanded in real life.

To prepare for our journey, I did a lot of reading about the state—its history, its beautiful yet challenging ecology, and the current demographic and economic situation. While Mississippi has a complex history—from ancient times, to the era of slavery, to the launching of the Civil Rights Movement, up to the present—a constant is its cultural vibrancy. Along with the Mississippi Writers Trail, the state boasts a wide range of impressive art museums, galleries, and theaters, and a legendary legacy of contributions to American music: Delta blues, jazz, country, rock n’ roll, gospel, and, of course, Elvis. We visited many sites on this trip, but I have chosen just a few to share with you.

Traversing the Natchez Trace

We began our trip in Natchez, driving north to Oxford and stopping at a number of sites along the Natchez Trace. (We decided to save the Delta for another trip. I’ll keep you posted on that.)

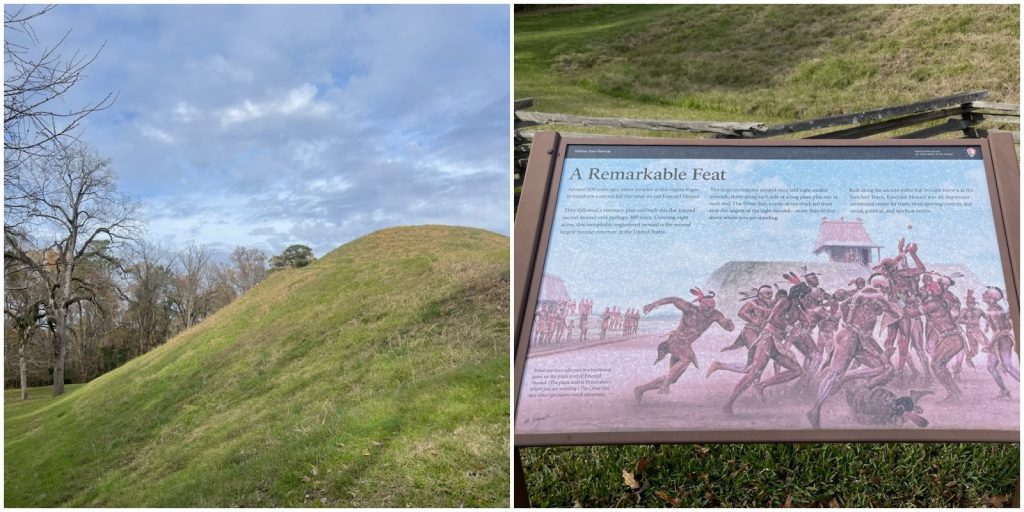

Emerald Mound

Originally known as Selerstown site, the mound’s current name was derived from an antebellum-era plantation that was nearby. Emerald Mound and the secondary mounds are similar to those we visited in Macon, Georgia, which I wrote about last January. It is the second largest mound structure in the country. Various excavations between 1838 and 1972 unearthed animal remains, ceramic fragments, tools, and stratigraphy, which have been studied by National Park Service archeologists. (As a side note, I love the idea of “stratigraphy”—“the branch of geology concerned with the order and relative position of strata and their relationship to the geological time scale.” The whole idea of this ignites all sorts of ideas and echoes eras of human history.) As we viewed the mounds and surrounding panoramic landscape, we could almost envision the lives of the people who inhabited this region.

Time-leaping forward to Longwood

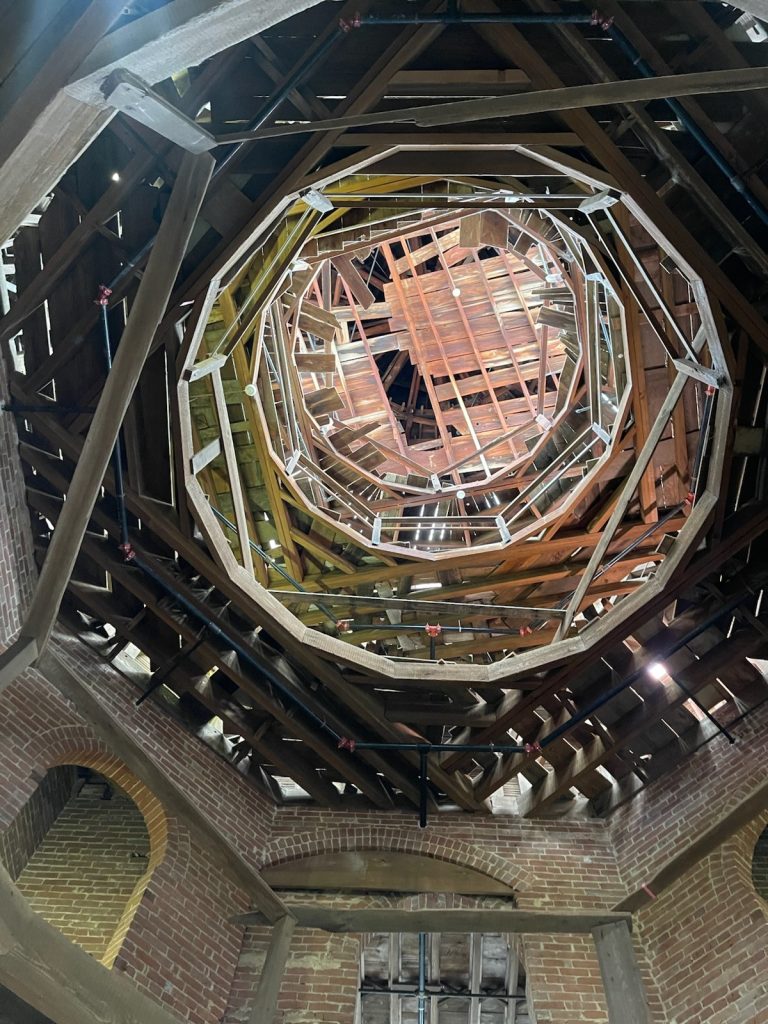

We then leapt forward hundreds of years to Longwood, one of Mississippi’s most famous antebellum estates. Longwood is a historic, octagonal mansion built by enslaved people in 1859. It was commissioned by cotton baron Haller Nutt, and as a result is also known as “Nutt’s Folly.” Construction was never completed due to the Civil War, the family’s resulting financial ruin, and Nutt’s death in 1864. Even though it is incomplete, it is on the National Register of Historic Places and is a National Historic Landmark. And…it is the largest octagonal house ever built in the U.S. (Another time I’ll delve into octagon structures, as there are several throughout New York State, including two very close to me—a house in Oneonta and a historic barn in Richfield Springs—and I find them fascinating.)

Longwood was designed by the Philadelphia architect, Samuel Sloan. Only nine of the 32 rooms—all on the ground floor/basement—were ever completed. The family lived on this lower level during the Civil War, and Haller’s wife, Julia, raised and educated her children there until her death in 1897. Grandchildren owned Longwood until 1968, and it was deeded to the Pilgrimage Garden Club in 1970, which operates it as a historic house museum. I think the architect was a phenomenal genius, and this was certainly unlike anything else when it was built in 1840.

Ground zero in the fight for Civil Rights

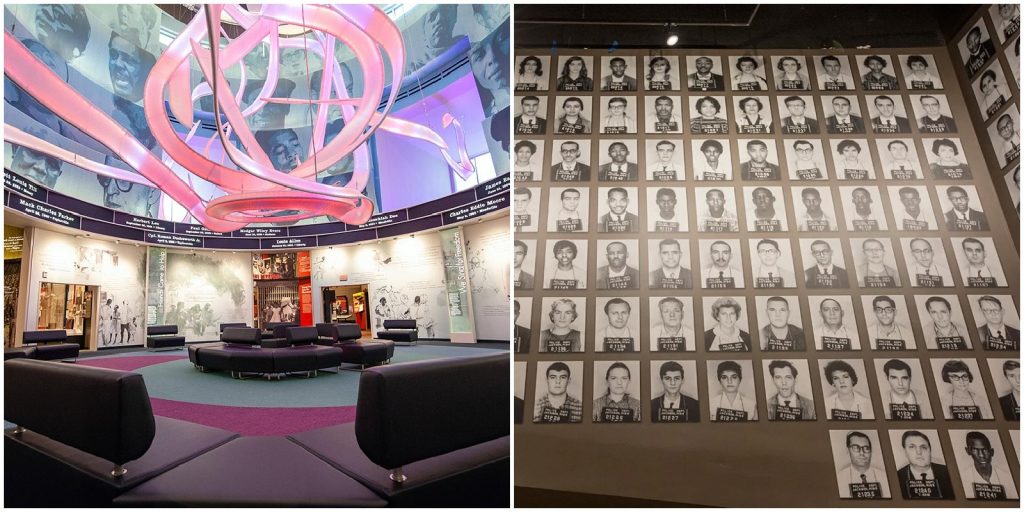

A highlight of our trip was the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum. This was the first museum dedicated to the U.S. Civil Rights Movement to be established, funded and administered by a state. The Mississippi Legislature approved funding for it in 2011, and it opened in 2017 to coincide with the state’s bicentennial. Leading the building’s design team was the renowned African American architect, Philip Freelon, perhaps best known to many as leading the design team for the Smithsonian’s stunning National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, which I have visited many times and continue to visit.

This museum is part of an interconnected, two-museum complex with the Museum of Mississippi History, which exhibits 15,000 years of culture. “The museums take visitors through the sweep of Mississippi history and the State’s role as ground zero in the U.S. Civil Rights Movement.”

Purely by accident we ran into Michael Morris, director of the museums, who shared insights into the various collections. He explained that Philip Freelon designed the eight galleries as a circle, and each “piece of the pie” represents a different time period, with a central atrium where one can reflect. It is a very powerful and visceral experience and well worth the trip to Jackson. Among the most moving inclusions are the “mug shots of every Freedom Rider arrested in Mississippi” and the “stories of civil rights veterans such as Fannie Lou Hamer, Vernon Dahmer, and Medgar Evers.”

(Last January, when I wrote about our prior trip through the South, I included our stop at the International African American Museum in Charleston, South Carolina, another outstanding museum, and on a future trip to Tennessee, we plan to take in the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis.)

After spending time at the museum, we enjoyed biscuits at Sugar’s Place, a delicious soul food restaurant on E. Griffith St. in Jackson that I highly recommend. For more Southern treats, see my Mississippi Mud Pie recipe later in this blog.

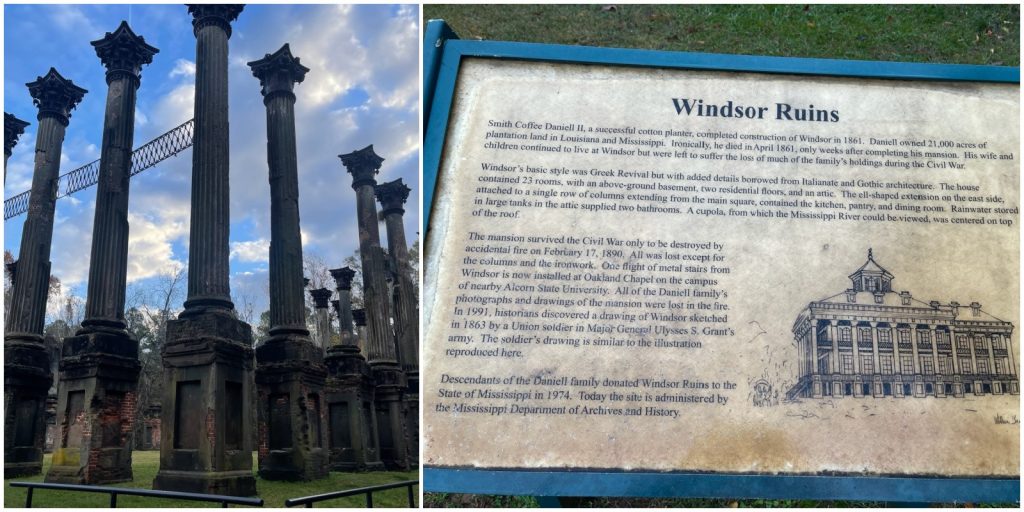

Windsor Ruins

Pivoting to Mexico

From ancient mounds in Mississippi to ancient ruins in Mexico.

What drew us to Yucatán were the ancient Mayan ruins at Uxmal, with its Pyramid of the Magician, Nunnery Quadrangle, House of the Turtles, and other romantically-named edifices that spark all sorts of imaginings about the civilization that built this city. (You’re probably wondering if we wish we’d pursued archeology instead of careers in law and opera!)

While less-visited than the more-famous Yucatán ruins at Chichén Itzá, the structures at Uxmal are equally impressive. The ornate, five-story Pyramid of the Magician is the tallest structure in Uxmal and is covered with intricate carvings not found elsewhere—like two-headed serpents with huge fangs, a jaguar throne, and homages to the Mayan rain god, Chaac. Like Chichén Itzá, Uxmal is also a UNESCO-designated site and is truly worth visiting. UNESCO describes, “The ruins of the ceremonial structures at Uxmal represent the pinnacle of late Maya art and architecture in their design, layout and ornamentation.”

There are two legends claiming the origins of the Pyramid of the Magician. In one, a magician-god used magic to erect the pyramid in a one night. In the other, a powerful dwarf magician was ordered by a king to build it within a fortnight or lose his life. There are apparently other spin-offs of these tales involving sorceresses, and one in which the dwarf is a boy who grows up overnight. The origin of the name “Uxmal” itself is questioned and either means “three times built” or possibly “what is to come, the future.”

Back home in the kitchen: Cooking up some Mississippi Mud Pie

Having directed “Show Boat” several times, I have a deep affection for “Old Man River” and the romance of the mighty Mississippi. Although it ranks second in length to the Missouri River, it is more than 11-miles wide near Bena, Minnesota, and has the third-largest river basin in the world, behind the Amazon and the Congo basins. And another bit of kitsch: it claims to be the birthplace of waterskiing, in 1922. (Thoughts of waterskiing bring to mind the wonderful Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who often went waterskiing on Otsego Lake during her trips to Cooperstown for opera well into her senior years.)

The name “Mississippi mud pie” is derived from a dense cake that resembles the banks of the river. Its earliest known reference in print is dated 1975. Mississippi mud pies may have begun in the 1970s as a variation on “mud cake,” a dessert that was popular in the American South during World War II. Another story says that Mississippi mud pie may also have originated from the Vicksburg-Natchez area in the 1920s. In this version, a woman named Jenny Meyer worked as a waitress there after having lost her home when the river flooded. During one of her shifts, the waitress noted that a melting chocolate pie resembled the Mississippi River’s muddy banks, which is how the dessert gained its name.

So, fascinated with the river, the musical, and our trip to the Magnolia State, I had to take a shot at making a Mississippi mud pie. It is very rich and gooey, so get ready! I tried a bunch of recipes and this is the one I liked the best. Be patient; with chilling time, this takes 4-4-1/2 hours to complete, but it doesn’t involve high-level pastry skills.

Mississippi Mud Pie

INGREDIENTS

For the crust:

4 tablespoons unsalted butter melted

1-3/4 cups Oreo cookie crumbs or other chocolate sandwich cookie (approx. 24 cookies)

For the fudge layer:

4 tablespoons unsalted butter cut into tablespoons

1/2 cup granulated sugar

1/2 cup Dutch-process cocoa powder, Hershey’s special dark cocoa powder recommended

1/2 cup heavy cream

1/8 teaspoon salt

1-1/2 teaspoons vanilla extract

Final layers:

1 (48-ounce) container coffee fudge ice cream or chocolate ice cream

1 3/4 cup heavy cream

3 tablespoons powdered sugar

1/2 teaspoon vanilla extract

1/8 teaspoon salt

2 to 3 Oreos optional, for topping

INSTRUCTIONS

Oreo Crust:

• Preheat oven to 350°F (175°C). Lightly grease a 9-9.5-inch pie pan with cooking spray.

• Melt the butter in a microwave-safe bowl. Once melted, set aside to cool for 5 minutes (excess butter may cause a greasy crust).

• In a blender or food processor, process the whole cookies (don’t separate the cookie from the cream) until they turn into fine crumbs (re-blend any large chunks). Measure the crumbs and add them to a large bowl.

• Add salt.

• Use a spatula to scrape in every bit of butter and mix until well combined.

• Pour the crumb mixture into the prepared pan. Using your fingers, press the crumbs into the bottom and up the sides. Use the bottom of a flat 1-cup measuring cup to compress the crumbs into a firm crust.

• Bake for 10 minutes, then remove from the oven and let cool completely.

Fudge:

• Meanwhile, prepare the fudge. Cut the butter into 4 equal-sized slices and place them in the bottom of a heavy-bottomed medium pot.

• Place over medium heat and add the sugar, cocoa powder, heavy cream, and salt.

• Using a whisk, mix briskly until the ingredients are combined and the butter is fully melted.

• Remove from heat. Whisk in the vanilla extract. Let it stand to cool (it will thicken as it cools).

• Assemble Pie:

• Add 1/2 of the fudge mixture to the cooled pie crust, and gently spread it along the bottom into an even layer. Freeze for 10 minutes.

• Then add scoops of ice cream, gently compressing them into a solid, compact layer—you should use the entire container of ice cream.

• Smooth the top with the back of a table knife and place it in the freezer for another 10 minutes.

• Remove the pie and spoon small amounts of the remaining fudge all over the top. Gently spread it into an even layer—this takes some patience!

Whipped Cream:

• Use a stand mixer with a whisk attachment (or a hand mixer) to combine the heavy cream, powdered sugar, vanilla, and salt.

• Whisk on high speed until soft peaks form.

• Gently dollop the whipped cream and smooth it into an even layer over the fudge layer. Crush 2–3 Oreos to garnish the top.

• Freeze until completely solid, about 4 to 8 hours.

Before signing off…

I want to take a moment to applaud the three composers/librettist teams who premiered their 20-minute commissioned operas in January through Washington National Opera’s American Opera Initiative (AOI). I am very proud of this program, now running for more than 12 years, through which competitively-selected emerging opera librettists and composers are given the opportunity to develop a short work under the mentorship of renowned composers and librettists (this year, acclaimed composer Gregory Spears and former U.S. Poet Laureate, playwright, librettist Tracy K. Smith). Each January, the awardees premiere their pieces at the Kennedy Center, and this year I was thrilled that we were able to add a performance at Merkin Hall in New York City (with special thanks to Kaufman Music Center Director of Artistic Planning, John Glover).

Huge thanks and kudos to the director of the American Opera Initiative, Christopher Cano, the program’s artistic advisor, librettist/dramaturg Kelley Rourke, and all of the artists. To read more about this year’s winning talent, their operas, and the impressive impact of the program, please check out this story from the Kennedy Center’s CENTERBLOG.

A few fun facts about AOI:

- As of November 2024, AOI has commissioned 36, 20-minute operas.

- In its first decade, AOI commissioned seven hour-long operas, six of which have had 25 additional performances across the U.S.

- As of December 2023, more than one-third of the 20-minute operas commissioned by AOI have been picked up by other companies.

- At least 15 of the teams commissioned in the first decade of AOI have continued to work together.

- After the early training they received through AOI, alumni composers and librettists have gone on to contribute more than 55 operas to the American repertory.

And please consider a trip to D.C. (and let me know if you are coming) to see what else we are doing at Washington National Opera.

Thank you, as always, for following me and my travels, and I’d love to hear from you about your own journeys.

Warmly,

‘Cesca

Francesca Zambello is the artistic and general director, emerita of the Glimmerglass Festival. She currently holds the position of artistic director at the Washington National Opera at the Kennedy Center. She travels the globe as a freelance opera and theater director and makes her home in Richfield Springs with her family. “Travels with ‘Cesca” is excerpted from “Francesca’s Traveling iPad,” an e-newsletter that has been ongoing since 2011.