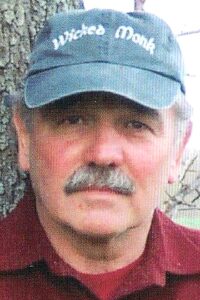

LETTER from TERRY BERKSON

Lady With Horse

I heard about Lady Ostapeck about 20 years ago at my friend Buddy Crist’s house on Angel Hill outside of Schuyler Lake.

There was a picture hanging on his living room wall. It was of a man dressed in a Tolstoy-like shirt standing in the doorway of a weathered cabin.

When I took a closer look I realized it was Buddy, appearing very authentic in clothes I never saw him wear before. “Who took the picture?” I asked.

“Her name is Lady Ostapeck,” Buddy answered. “I was gassing up in Richfield Springs. She was filling her tank on the other side of the pump and kept looking at me. I mean really looking – for a long time. Finally she comes around the pump and says, ‘Are you finish?’”

“I’m still pumping,” I answered.

“No, are you Finnish – from Scandinavia?” she asked.

“I don’t think so.”

“That may be, but I’d like to take your picture.”

It turned out that the woman who was then in her seventies was a famous photographer of Finnish descent. She wanted Buddy, who had the “right look,” to pose for pictures she planned to use for Independence Day in Finland.

They made an appointment, and a week later my friend spent an entire day trying on clothes in a costume – and prop-cluttered house while talking with Lady Ostapeck as she tried to bring to the surface a certain spirit she saw in him.

When his wife Cathy, who had been sitting in their car for hours, came around to see how the photo session was going, Lady ushered her away, saying that her presence would affect the aura.

Each shot took a long time. Lady would remove a makeshift velvet-lined bottle cap that she used to cover the lens of her antique Korona box camera. Then she’d start counting exposure time out loud. The speed of the count depended on the light that was coming through a nearby window.

In an attempt to repair the camera’s broken shutter, she had taken it completely apart but was unsuccessful in making it work. When it was time to reassemble the damaged instrument she lubricated the screws with oil from the back of her ear. She also used spit in some places.

Though the shutter remained broken, the repair procedure lent to the mystic approach she brought to her photography. Lady believed the resultant portrait, accented by the use of costumes, lighting and conversation would reflect something from a sitter’s soul.

Lady Ostapeck, whose birth name was Alma Kaukinen, was born in Brooklyn. Her mother died a few days after she gave birth and her father, an immigrant from Finland, left the newborn baby in the care of her mother’s sister.

He fled to the Northwest to work as a lumberjack and avoid the World War I army draft. Incredibly, two years later, the aunt taking care of the child was murdered along with the rest of her family by a deranged neighbor. The child was spared and later passed through several Finnish families before she wound up in the mothering care of a widow by the name of Jansson who lived in New Jersey.

As an adult, Lady worked at retouching negatives and photographs for studios in New York City. The work was piecemeal and enabled her to answer a “calling” to frequently visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Commuting across the Hudson by ferry allowed her to maintain residence in New Jersey.

She married Peter Ostapeck and had one child, a boy. The marriage lasted about five years. She later stated that she wasn’t cut out to be an ordinary housewife.

The “Lady” part of her life started when she put an ad in a newspaper stating, “Lady with horse wants house.” The appeal resulted in her finding an abode along with barn in the tiny hamlet of Fly Creek. It was then that she bought a horse and gave it a Finnish name that sounded risque in English.

She continued working for the studios in Manhattan but a lost portrait resulted in her termination. It was in 1970 that she bought the Korona with the broken shutter. The purchase turned out to be her first step on the long road to international fame as a vintage photographer.

Fame did not come with fortune, but over the years Lady managed to make at least a dozen trips to Finland where her work was well received.

Finns first assumed that the accomplished artist was self-sustaining – and in her own way she was. Once, a government official arranged for her to make

the expensive voyage as a courier.

A shopping bag was all she needed to carry her belongings.

In lieu of having to pay for lodgings she sometimes slept on a train. If the weather grew cold a slit in an old blanket made a poncho. She had an aversion to throwing broken things away.

In Lady’s words: “Forty years doing negative retouching does not teach one to be a photographer … I became a photographer anyway.”

Several years ago I met Lady Ostapeck at the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown. While we were talking I got the feeling that she was checking me out in much the same way she did Buddy years before at the gas station.

At one point she asked if I had ever been on the stage to which I responded, no. The last thing she said to me was, “Come up and see me some time,” which I took to mean that she wanted to do a portrait. Regretfully, I never responded to her invitation.

Lady’s funeral was held on the 8th of February, 20 days before her 99th birthday. James Atwell, the Quaker minister, presided over the impressive ceremony. Friends spoke of a triumphant life in spite of tragic beginnings, and of Lady’s possessing a curiosity that outweighed fear.

I have never attended a funeral where mourners broke into applause from descriptions of her style and attitude towards life. In response, she’d probably say, “Keep a straight face when you think of me. Smiles don’t hold up for an extended exposure time.”