THE NIGHTINGALE & THE FIREFLY/PART II

Chance, Romance

Change Everything

Editor’s Note: This is the second article in a three-part series on Ashok Malhotra, who retired in December after almost a half-century in SUNY Oneonta’s Philosophy Department. In was published in Hometown Oneonta & The Freeman’s Journal on March 3-4, 2016.

By JIM KEVLIN • for www.AllOTSEGO.com

ONEONTA – His first snowstorm, magical white flakes falling out of the night sky: It was a pivotal point in his life.

“It was like being in heaven,” Ashok Malhotra remembers.

It was Dec. 21, 1965, and he and Nina Finestone, after cleaning up from his 24th birthday party, had just left the apartment near the NYU campus where he rented a room.

Just three days before, Ashok and a pal – another foreign student – had been chatting in the snack bar in the basement of the Loeb Student Center. “The door opens,” he remembers, “and a beautiful woman walks in.”

“Are you people from Pakistan?” she asks.

“No, we’re from India,” he replies.

“Do you have four wives?”

No, he explains, Indians are mostly Hindus – one wife. It’s the Moslems, in Pakistan, who are permitted more than one.

Ashok ends up buying her French fries, and they talk from 2 to 8 p.m. They walk out into Greenwich Village, and were still walking and talking at midnight.

She calls the next morning: “I’ve been thinking of you; I’ve been missing you.”

He replies, “I’ve been missing you, too.”

A few days later, they meet at 11 p.m. at Café Feenjon, a Turkish restaurant in The Village. “Get up,” the proprietor tells them, “and you can sing with us and dance with us.”

“Hours passed, eating and dancing,” Malhotra remembers.

As they left at 3 a.m., Nina turns to Ashok: “I’ve fallen in love with you. And I’m going to marry you.”

“Wait a minute,” the surprised suitor replies. “We just met a week ago. You don’t even know me.”

“No,” she says emphatically. “I’ve decided: I’m going to marry you.”

•

Ashok Malhotra, founding professor of SUNY Oneonta’s philosophy department – he retired in December after 47 years at the college – was born in 1941 in Ferozepur, three miles from India’s future border with Pakistan. With 10 brothers and sisters, his parents and grandparents, he grew up in a tranquil daily domestic round he never expected to end.

But it did, abruptly, with riots and looting that followed The Raj’s end on Aug. 15, 1947, and a devastating flood the following year that covered Ferozepur to 14 feet and drowned the family’s 10-cow herd. His father, Nihal Malhotra, discouraged and depressed, abandoned the family.

Grandfather Hari C. Chopra, a retired stationmaster, had built three houses, and the rent from two of them provided a meager income. His mother, Vidya, made an arrangement with a jersey factory to obtain the cloth pieces removed when leather patches were sewn on the elbow.

At home, 2-3 hours a day, as her children turned the crank on a manual sewing machine, she would craft the pieces into outfits for newborns.

Krishan, the oldest of Ashok’s eight brothers, got a job teaching economics at a local college to help support the brood. “The family was OK,” Malhotra remembers. “But it was barely meeting ends.”

At 10, Ashok entered high school, and a “transforming experience” occurred. There were 60 students in his class. The teacher began handing out the graded tests. “He’s going from the best to the worst,” the anxious young man told himself. He returns all tests, except Ashok’s.

“Come over here so everyone can see you,” the teacher told the boy.

“I wanted to run,” said Ashok.

“Turn around the look at the class,” the teacher ordered.

Pause. “Don’t you every forget him,” said the man at the head of the room. “He’s got the highest grade in the class. Come on. Clap.”

“The whole class is applauding,” Malhotra recounted, 65 years later, in an interview at his Center Street home. “I couldn’t believe it. I felt so nervous. I also felt so elated – to be on top of the class. I can do something! I made up my mind: I’m never going to let my teacher down.”

He went through high school with the highest GPA, plus playing field hockey and achieving “top bowler” – ace pitcher – on the cricket team. On graduation, “I could write my own ticket.” He was accepted at BITS, India’s MIT, the Birla Institute of Technology & Science. (G.D. Birla, India’s Rockefeller, established the national university.)

After two years, he ran out of money and had to drop out of school. He sought out his father, now a molasses vendor in Kanpur, in Uttar Pradesh, east of Punjab. “If you go to college, I want nothing to do with you,” was his father’s welcome. “Going to school gives you ideas.”

Molasses, piled in a room of Nihal’s tiny sweltering house, stank. After a few months, Ashok and a friend ran off and joined the Indian Air Force. Realizing he’d made a mistake, he was able to talk his way out of a 15-year commitment a year later.

With a little money in his pocket, he returned to BITS, where he began tutoring wealthy students in calculus – “one of my favorite courses” – and paid his way through college. “The next four years, life became easier.”

He graduated and went on for a master’s, influenced by a Dr. Sinha, a “very vibrant, very special” professor who guided him into philosophy, which – in India at the time – tilted heavily toward psychology, Mesmer, Freud, Adler, Jung. And Behaviorism: Kafka, Skinner, William James. “I could understand my mind!” As it had been since his fellow students applauded in Ferozepur, “I had the highest GPA in the whole university.”

•

By this time, he was a prefect – the British system’s version of an R.A. – sitting in his room, when his professor of Hindi hurried in with a newspaper clipping: The USIA (the now defunct U.S. Information Agency) was announcing an “all-Indian competition” – “350 million people,” Malhotra marvels – for scholarships to obtain Ph.D.s from its East-West Center in Honolulu. “Of all the people at BITS, you are the only person who can get it,” Professor Sharma told him.

“I couldn’t refuse,” said Ashok. “I respected my teacher.” So a week later, he was on the train to distant Delhi – reading Bram Stoker’s “Dracula,” he remembers – where he rented a floor space in the railroad station’s “guest house,” 5 rupees a day.

The next morning, he makes his way to the interview, stationing himself in a waiting room. 9 a.m., 10 a.m., noon, 2. He waits all day. Finally, at 4, “I’m the last one; everyone else is done,” and he’s summoned through the door. There’s an oval table, 10-11 people grouped around an elegant, white-haired woman.

One chair is vacant. He sits down. The woman walks over. “She picks up a cigarette. Lights it. Blows it in my face.”

“If someone did this to you, what would you do?” she asks.

“My blood was boiling.” He said to himself, “I’m not going to be selected anyway.” So he reached for the cigarette, inhaled, and blew the smoke back in her face. “Everybody cracked up,” he recalled.

The questions began and – by happy coincidence – just about all dealt with issues he’d just read about or studied. Why was the Chinese army beating the Indian one in the Himalayas? Because the Chinese had trained in the icy mountains; the Indians – “they are freezing their toes off” – on the sweltering plains below.

What did he know about a radical philosophy gaining a European following. Existentialism! Dr. Sinha had introduced his students to Sartre and Camus just weeks before. “It was just like someone was helping me,” he remembers.

When it was over, they all stood up: He had the scholarship – four years education, all paid; plane ticket, all room and board, and a monthly stipend, no strings attached.

And so, the young lad who watched killings and looters from his family’s home, destitute after a huge flood thrust his family into poverty, awakened one night in the heat and stench to find a giant bull rubbing against his cot while feeding on molasses, found himself on Sept. 9, 1963, aboard a Pan Am jet, after 17 hours in the air, approaching Honolulu International Airport.

“The world is what it is,” he reflects. “You don’t have any control.”

He had $8 in his pocket. What if no one meets him? A Thai girl from the East-West Center does. She puts a lei around his shoulders and kisses him on both cheeks. “It’s a first time that any girl had given me a kiss.”

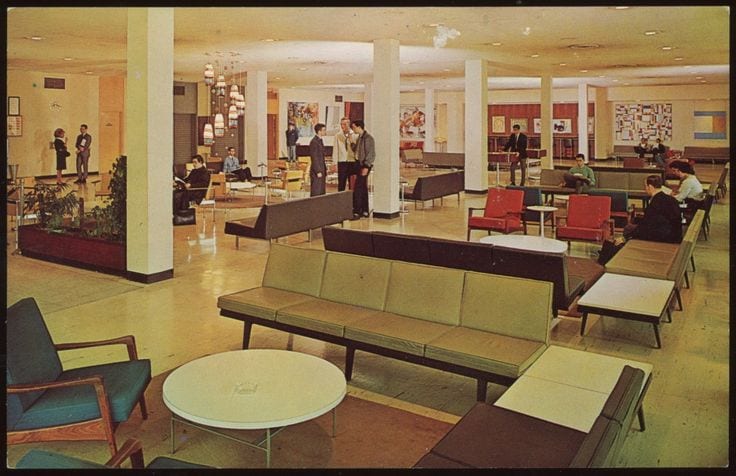

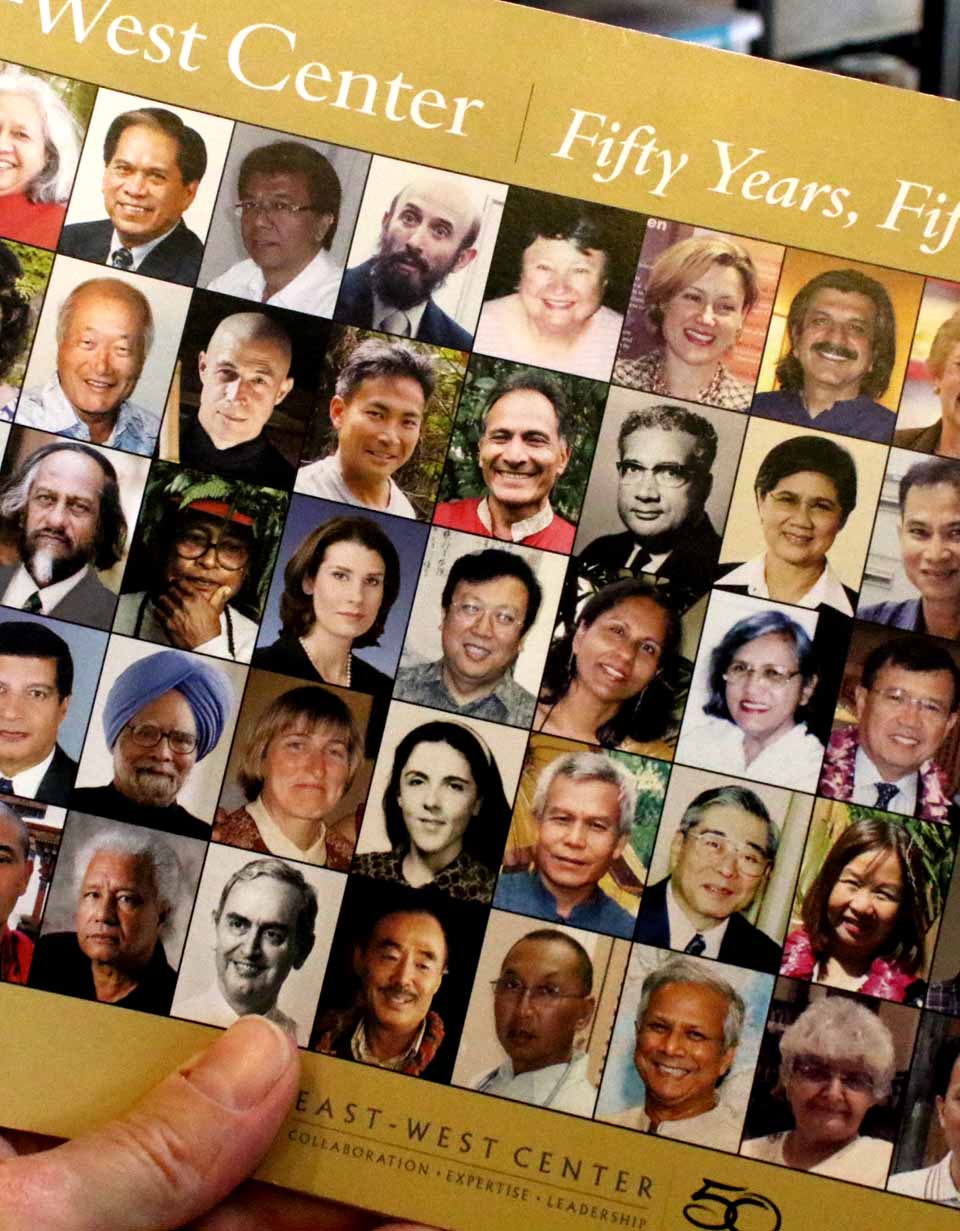

He joined dozens of students from throughout Asia, recruited to the East-West Center with the idea they would gain their Ph.Ds., absorb American culture and democracy, and return to take leadership positions in their homelands.

(At the time, the program cost $50,000 per student, for a reason. The story is that Eisenhower asked after Korea stalemated: How much did it cost to kill one soldier? The answer: $50,000. “So that’s the price of defeat?” the president asked ruefully.)

“That’s when all the fun started.” En route to the campus, a rainbow appeared. “I am in paradise,” Ashok thought to himself. “I’m going to stay here forever.”

He was paired with a U.S. student – in his case, David Ishizaka, from Wisconsin. (Barack Obama Sr., from Kenya, was in the program earlier. He met Stanley Ann Dunham there in 1961, married her; they divorced after three years, but not before the future president was born.)

Because of the psychology emphasis at BITS, ever-over-achieving Malhotra had to complete his master’s philosophy requires, plus doctoral ones: He took 66 credits in four years, instead of the required 30.

The students made time for fun, learning about each other’s countries through weekly “cultural nights.” Ashok taught his fellow students the bhangra, a rowdy dance from rural Punjab. In annual reunions that continue until this day, the East-West alumni dance the bhangra and relive their cricket games.

“Why doesn’t the U.N. learn from us,” the students would ask each other. They were further stunned by how the poverty in which they were raised contrasted with the plenty they found around them.

“It opened up my mind,” said Malhotra. “I don’t belong to just Punjab. I’m a citizen of the world. I belong to no country. It made me a citizen of the world.”

All East-West students could spend a semester at a mainland campus – Harvard, Princeton. Malhotra, drawn by the beacon of New York City, chose NYU and, on that morning at the Loeb Student Center, met his future.

•

“Yes, I think you’re crazy too,” Ashok replied.

So, an only child, she took Ashok home to Stuyvesant Town to meet her Jewish parents in their apartment, above the roar of the Eastside Highway. Her father, Jack, was seated at the piano – “hello, how are you?” – and he continued playing Mozart as the suitor arrived.

The questions followed. Income? None yet. Intentions? Honorable. Are you a good person? “So far.” Finally, “Do you have four wives?” Reply, “I’m not even married.”

The next day, Rockefeller Center. “She taught me how to skate.” Central Park. Radio City. “The next 10 days, we saw each other every day. A whole world opened up in 10 days.”

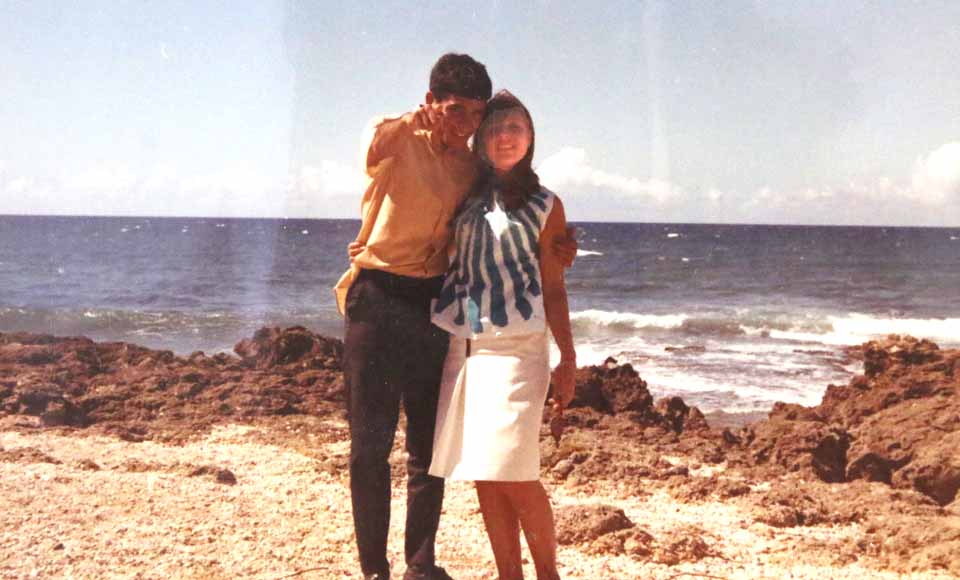

And so Ashok Malhotra returned to Honolulu in January 1966, with three semesters to go on his studies. “To keep our love alive, we wrote each other every day. I still have them,” he said, holding a palm out horizontally above his head.

And so to the travails of romance. She graduates from college in May, goes to Hawaii, goes home to a Head Start job, then back to Honolulu. The rabbi won’t marry them – only Jews with Christians or Moslems, People of the Book. Her mother won’t come; or her favorite aunt.

But dad does. A JP performs the ceremony, then rushes off to a football game on TV. A romantic celebration at Ilikai, a rotating restaurant above Duke Kahanamoku Lagoon – there’s Waikiki Beach, and Diamond Head, and the East-West Center campus, “the whole panoramic view.”

Champagne, wedding music (Don Ho), a couple of bottles of champagne, she had steak, he salmon, then a honeymoon trip to all the islands. “I exhausted my $210,” the groom remembers.

Then, back to reality. East-West graduates could spend two years teaching in the U.S. Job applications. A college in Texas is looking to start a philosophy department, and one in the Midwest.

And then, a letter arrives from Oneonta.