Graphic obtained from Hartmann, Helena, Jonas Potthoff, Livia Asan and Ulrike Bingel, “The Nocebo Effect: The Placebo’s ‘Evil Twin,’” in “Frontiers for Young Minds,” April 21, 2023, https://kids.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frym.2023.853490. Figure created using Canva, https://www.canva.com/.

Citizen Science No. 6 by Jamie Zvirzdin

The Power of the Placebo Effect, Part II: When Belief Brings Harm

Watch out! That medicine will make you sick! You’ll regret taking it!”

Words hold immense power over our minds and bodies. Just as Dumbo believed in the magic feather and flew across the circus tent—even after he learned the feather was a placebo, an empty talisman—our beliefs can shape our experiences in unexpected ways. However, there is a darker side to this phenomenon—the “nocebo” effect. Brace yourself as we now step into the darker shadows of the circus tent and explore the impact of negative expectations on the human psyche.

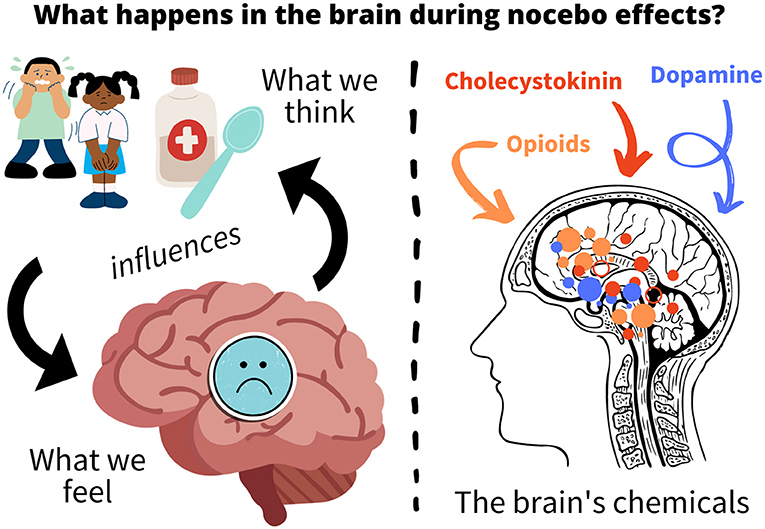

Derived from the Latin phrase meaning “I shall harm,” the nocebo effect is the evil twin of the placebo effect, which we talked about last month in “Citizen Science” (access past articles online at www.allotsego.com). The nocebo effect happens when we experience adverse symptoms or side effects after receiving a treatment—even from an inert substance, like an empty sugar pill. The pill harms us simply because we believe it will cause us harm. The mind’s ability to manifest these negative outcomes is a fascinating yet troubling aspect of our psychological makeup.

Similar to the placebo effect, the nocebo effect showcases the power of belief and expectation. Suggestion is king: When we are convinced that a treatment or substance will have harmful effects, our thoughts can trigger a series of physiological responses that actually help create those anticipated symptoms. The mind influences the body, and the body responds accordingly. You believe the medicine will cause you pain? Yes, it will, just because you believe it will. The nocebo effect was particularly problematic when the COVID-19 vaccine came out, since the presumed side effects were talked about so frequently among friends and in the media. I myself had been prepared to experience all the side effects of the vaccine, and I indeed experienced them all, one after another like a laundry list—but it is possible some of those side effects were psychosomatic, that is, induced by the self. This could be the nocebo effect in action. (To be clear, I’d take the vaccine again in a heartbeat, and we can talk more about the science behind vaccines in the future.) Wanting to avoid advertised side effects caused many people to avoid getting the vaccine, prolonging the spread of COVID-19 among us.

The nocebo effect manifests itself in other ways. For instance, if doctors tell us about potential side effects of a medication—as they should, because ethically, we patients need to be informed—we are more likely to experience those side effects, even if the medication itself is harmless. Those of us who strongly believe we are susceptible to allergies, for example, may experience allergic reactions when we are told about possible allergic reactions and then exposed to benign substances. It’s like Dumbo’s feather suddenly causes us to itch uncontrollably because we believe the feather will cause an allergic reaction.

Why should we care about the nocebo effect? For one, it may cause vaccine hesitancy. The nocebo effect can cause people to feel negative side effects that they might not otherwise experience, which in turn may cause their friends to avoid vaccinations. Healthcare providers must especially be mindful of the potential harm that negative suggestions can inflict on patients. Communicating information in a balanced manner, emphasizing the potential benefits alongside possible risks, can help ease the negative influence of the nocebo effect. Armed with this knowledge, medical professionals must navigate the delicate balance between transparency and the unintended amplification of negative outcomes. We need to make informed decisions about our health, but we also need to be aware that our own minds, our own negative expectations, can cause undue side effects. I never want to discount people who do, indeed, feel the side effects of a certain medication; yet we all should be aware that our own minds can betray us in this way sometimes. It is fascinating to wade into the deep end of medical trials where study participants, given a placebo but told they may experience negative side effects, do indeed feel pain after taking an empty pill. For more information, I recommend reading “Placebos,” a book by Kathryn T. Hall (The MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series, 2022).

As we step away from the shadows of the nocebo effect, let us remember the importance of fostering a positive and supportive environment in our pursuit of well-being. Join us in the next installment as we venture deeper into the captivating world of confirmation bias. Until then, may your beliefs bring you only the best in health and happiness.

Jamie Zvirzdin researches cosmic rays with the Telescope Array Project, teaches science writing at Johns Hopkins University and is the author of “Subatomic Writing.”