DIAL ‘O’ FOR MURDER

S.S. Van Dine’s Philo Vance Books

Took Him From Here To Hollywood

By LIBBY CUDMORE • Special to www.AllOTSEGO.com

ONEONTA – For a time, S.S. Van Dine was the biggest thing in detective fiction.

“He got famous fast,” said Michael Sharp, a Binghamton University English professor who specializes in American Crime Fiction. “He writes his first book and he immediately becomes a best-seller.”

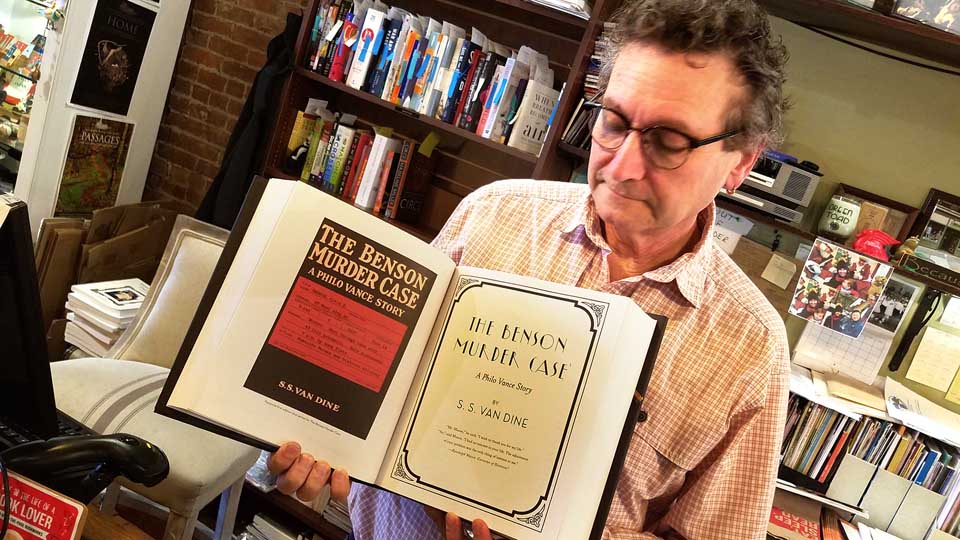

That first novel, “The Benson Murder Case,” published in 1926, is believed to have been written, at least in part, at 31 River St., where Willard Huntington Wright was staying with his aunts Bertha and Julia Wright, on a two-year bed rest recommended by his doctor to help him recover from a cocaine addiction.

Forgotten for decades, Van Dine/Wright, with the Salvation Army planning to tear down 31 River St. for a parking lot, is back in the news.

According to an essay by Michael Mallory in Mystery Scene Magazine, Wright’s doctor also recommended the writer, who had recently been fired as the editor of The Smart Set for his erratic and temperamental behavior, to dip into detective fiction as “light reading.”

“For someone who had once written, ‘There are few punishments too severe for a popular novel writer,’ it sounded like a dubious proposition, but to Wright’s surprise, he found mystery novels challenging and entertaining,” Mallory wrote.

And thus – on River Street, perhaps – Philo Vance was born.

“Vance is modeled on the Golden Age detective,” said Sharp. “There were a lot of British writers, Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, writing these locked-door, puzzle mysteries. Vance was just the American version of that.”

The puzzle mystery – also known as a “cozy” – is more about the complexity of the puzzle as a whodunit, where the detective is often hired by a wealthy client to solve the crime as a hobby, rather than a profession like a cop or a private eye. They feature less violence than the hardboiled pulps that came later, and are solved by logical deductions made by the detective.

As such a dilettante, Van Dine described Vance as “…unusually good-looking, although his mouth was ascetic and cruel…there was a slightly derisive hauteur in the lift of his eyebrows…His forehead was full and sloping – it was the artist’s, rather than the scholar’s, brow.

“His cold grey eyes were widely spaced,” Vance’s creator continued. “His nose was straight and slender, and his chin narrow but prominent, with an unusually deep cleft…Vance was slightly under 6 feet, graceful, and giving the impression of sinewy strength and nervous endurance.”

He was also well-educated, “…had courses in the history of religions, the Greek classics, biology, civics, and political economy, philosophy, anthropology, literature, theoretical, and experimental psychology, and ancient and modern languages” and was “a man of unusual culture and brilliance.”

“He’s this cut-rate Sherlock Holmes who is so smart and can reason things so well,” said Sharp. “He wears his university degree on his sleeve, he’s a scholar and there’s a sense that it’s intellectually aspirational for the reader.”

In all, 12 Philo Vance novels were published, lifting Wright out of his post-Smart Set firing and into a somewhat wealthy lifestyle.

And Vance’s unusual good looks, as described, set him up for the silver screen, where he was played by top movie stars of the time.

William Powell, who would later find success playing detective Nick Charles in the “Thin Man” series, based on Dashiell Hammett’s novel, played Vance in “The Canary Murder Case” (1929), “The Greene Murder Case” (1929), “The Benson Murder Case” (1930) and “The Kennel Murder Case” (1933).

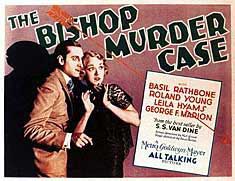

Sherlock Holmes’ most famous portrayer, Basil Rathbone, stepped into Vance’s role in “The Bishop Murder Case” (1930). In all, 15 Philo Vance movies were made.

In addition to Vance, Van Dine also created Inspector Carr and Dr. Crabtree, who investigated crimes in a series of a dozen 20-minute “two-reel” mystery films shown in theaters in 1931-32 before the feature.

But with the publication of Dashiell Hammett’s hardboiled classic “The Maltese Falcon” in 1929, detective fiction took a new tone, one much grittier and darker. Hardboiled mysteries began appearing in pulp magazines like Black Mask, bringing crime fiction to working-class readers.

“It was a more realistic depiction of how and why people commit crime,” said Sharp. “It used the language of criminals, cops and detectives, so there was no longer a market for that kind of puzzle mystery.”

As such, Philo Vance’s days were numbered.

“Van Dine did not have an afterlife, like Agatha Christie,” said Sharp. “It’s very dated, it satisfied the taste at the time, but tastes changed. And he wasn’t as good a writer as Christie or Sayers.”

“The Big Sleep” author Raymond Chandler mocked Vance at every opportunity, calling him “the most asinine character in detective fiction” in his essay, “The Simple Art of Murder.”

Part of it, Sharp theorized, is because Van Dine himself was ashamed of the work, but knew that it was what kept him in the wealthy lifestyle to which he became accustomed.

“The fact that he used a pseudonym tells you everything about how the author was regarded and how the books were regarded,” he said. “The notion that they were cheap and easy, so they were never real literature. Authors like Chandler tried to legitimize the genre.”

Van Dine died on April 11, 1939, in New York at age 50, of a heart condition likely brought on by excessive drinking, leaving behind an unfinished manuscript that would become the “The Winter Murder Case.”

Though reprints of his books aren’t difficult to find online – “The Benson Murder Case” was reprinted in “Crime Fiction of the 1920s,” available at The Green Toad Bookstore in Oneonta – Sharp said they are more a curiosity than a good read.

“He’s frozen in amber,” said Sharp. “People who are aficionados know him, maybe even like him, but you can walk into any bookstore and get an Agatha Christie novel, you can’t with Van Dine.”

I note that some “out there” have started writing of the “Philo Vance” mysteries more positively – this having been virtually unheard of for decades! I discovered the series in my teen years, and, some moons later, was delighted to find, when rereading the “Greene”, “Bishop” and “Dragon” “murder cases”, these to be as impressive as I’d initially considered them! Writer Van Dine could be overly pedantic in places, but for sheer uneasiness and spooky atmosphere, I know of no mystery literature, by any of the Golden Age writers of such, that equals that of the three titles cited above, with – respectively – the ominous old Greene mansion, nursery-rhyme serial killer, and ancient, glacier-formed dragon pool. When Van Dine was critically faulted for featuring too many murders in his novels, he responded by having but one homicide in his “The Scarab Murder Case” (1930) – a rather preposterous criticism to begin with; for where, to cite but one example, would Agatha Christie’s 1939 masterpiece, “And Then There Were None”, have been with only a few deaths rather than ten!

My “comment is awaiting moderation”? Rather as S.S. Van Dine was recommended to apply “moderation” to his fictional bloodletting – and no less ludicrous!