WHAT TO DO THIS WEEKEND

Exhibit At Monastery

Brings Faith Of Fathers

To Life In Jordanville

►IF YOU GO: Take Route 167 six miles north from the traffic light in downtown Richfield Springs to Holy Trinity Monastery. You can’t miss it. “Revealing The Divine” is open 10 a.m.-4 p.m., Tuesday-Saturday; 1-4 p.m. Sunday through Dec. 31

By JIM KEVLIN • Special to www.AllOTSEGO.com

JORDANVILLE – When you think of Russian art, you probably think: icons.

“It goes far beyond that,” Michael Perekrestov, Russian History Museum executive director at Holy Trinity Monastery here.

The museum’s new exhibit, “Revealing the Divine: Treasures of Russian Sacred Art,” proves it. The objects on display range from, yes, icons, to pendants, books, architecture, vestments and much more.

The exhibit opened July 14, and will be on display at the monastery’s museum, just 18 miles north of Cooperstown, through the end of the year.

Of course, Perekrestov, who put on the nationally known “Last Days of the Tsar,” artifacts from the Romanovs, in 2018 – the 100th anniversary of the massacre of the imperial family – has favorite pieces in this exhibit, too.

His favorite, the “Amethyst Panagia,” a gold and silver medallion encrusted with amethysts and diamonds, worn by bishops on ceremonial occasions. In the central jewel, look closely and you’ll see a delicately etched image of the Virgin Mary.

It was created by Jahn & Bolin, a St. Petersburg jeweler whose creations for the Russian court rivaled Faberge’s.

“It’s an extraordinary piece,” said the curator, brought to the U.S. by Bishop Feofan Gavril when the White Russian Army collapsed, the Bolsheviks were in ascendance, and he joined the first Russian diaspora.

The diaspora not only brought refugees to this country, they brought treasures with them, many hundreds of which have been willed over the decades to the monastery – it is one of the centers of the Orthodox Church in the U.S.

This exhibit draws on 12 collections from around the Northeast, including the Byzantine Catholic Eparchy of Passaic, N.J. and a private collection in Virginia.

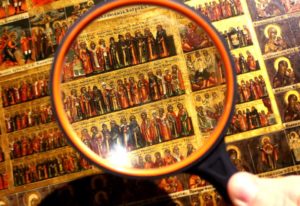

A close second is Mineya Icon, a 30-by-30-inch calendar on wood built around a central image of Christ’s descent into Hell. It is bordered by 12 segments – the months of the year – each containing tiny painted figure saints, one representing each day.

“I have no idea how long it would have taken the iconographer to paint this,” Perekrestov said.

A third? “Bishop’s Sakkos,” a brocade, silk, velvet, sequined, with paste gemstones and brass fittings, that Julien Bryan, a famed World War II filmmaker (the only independent photographer there when the Nazis invaded Warsaw) bought for a song in the gift shop at Moscow’s National Hotel in 1935.

(The Soviet Union, Perekrestov explained, would sell seized church artifacts to obtain foreign currency.)

Bryan returned to the U.S. through the Far East, intending to cut up the Sakkos and like garments for other uses. Arriving in Seattle, the Customs’ agent “was floored by the quality of these pieces,” the curator said.

“These are museum pieces,” the man told Bryan. “You need to keep them the way you are.” And so the vestment was saved.

Though the monastery, with its gold domes and minarets, seems timeless, the coronavirus threat has brought innovation, even here, in the form of Second Saturday virtual lectures.

The third, on July 11, featured Nick Nicholson, the monastery’s director of development, lecturing on “Black Gold: Russian Lacquer, 18th-20th Century.”

“People watched from all over North America, the U.K., Russia, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia – and Namibia, of all places,” Perekrestov said with surprise.

“Revealing the Divine” features 160 objects in all, including photographs of objects being seized by Soviet troops and contemporary icons and paintings.

But it’s the earlier work that captivates Perekrestov.

“When people say art, we think of self-expression. That’s a modern notion,” he said. “Most art is very closely connected to religion – art didn’t exist outside the religious context. “That’s eye-opening for many people.”