FAM Exhibit Teases, Tickles, Taunts the Imagination

By TERESA WINCHESTER

COOPERSTOWN

Lewis Carroll’s Alice went down a rabbit hole to be transported to a world of wonder and strangeness. Something similar happens when visiting Fenimore Art Museum’s exhibit, “A Cabinet of Curious Matters: Work by Nancy Callahan and Richard Whitten.”

Museum goers should plan to spend a long while in the gallery. These works cannot be fully appreciated in a casual stroll-through. Each piece is the product of an active imagination, requiring the active participation of the observer’s imagination as well. Trompe l’oeil, visual puns, whimsy and even trickery are part and parcel of the show. As in our dreams, the real blends with the unreal, continually confounding our perceptions.

The works of Callahan and Whitten are uncannily complementary. Museum notes state the artists “share an interest in dreams, antique scientific and medical instruments, mythologies, and mysteries.” Despite their common interests, however, Callahan, retired professor Emerita at SUNY-Oneonta, and Whitten, professor of painting at Rhode Island College, go about their work in a polar opposite manner.

“Like a dreamer letting down their guard for the night, I give myself over to the work in the studio day after day not knowing where it will take me. There are no carefully drawn sketches, thoughtfully formed plans or even a map to guide the way,” Callahan writes in a catalog of her exhibit.

Conversely, Whitten methodically works out each drawing before finalizing it.

“I draft out the piece, then make notebook drawings, then make a model,” Whitten said in a talk at the museum.

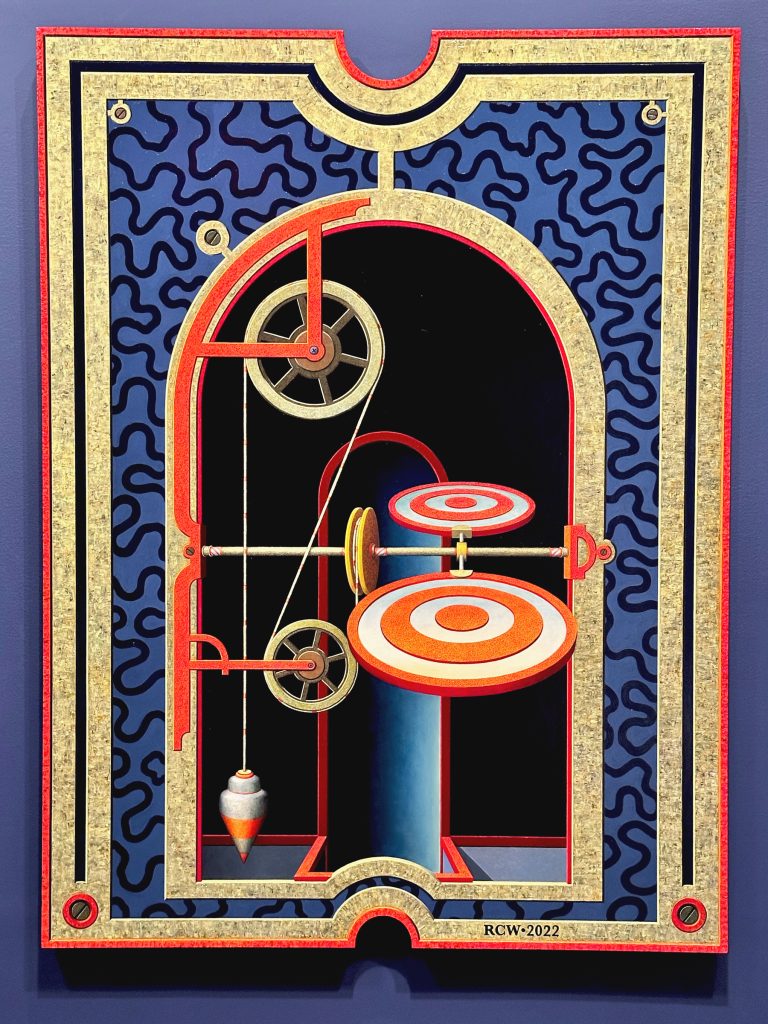

Whitten’s paintings, largely oil on wood panel, reveal a fascination with architecture, invented machinery and toys. Although one-dimensional, they often convey depth and movement. His “frames,” architectural in character, are an integral part of the paintings themselves.

Whitten’s “Air Paddle” reflects his interest in the mechanical and his penchant for playfulness. The precision and starkness of his pulley and plumb bob, strung with rope through bobbins, strangely project realism. Yet for what purpose would anyone devise such a contraption?

“Caccia,” Italian for “hunt,” features a mechanical device posed on what looks to be a vintage schoolroom desk or a Victorian table. A medallion with a cat face is fastened to what could be a stereo needle. A wire, evoking a mouse’s tail, is attached to the needle. At the end of the wire is another medallion containing a mouse’s face, suggesting that a “cat-and-mouse” game is at play, all the more so since “caccia” is onomatopoeic for “catchya.” Word play adds to the visual tease of this piece.

While Whitten works one-dimensionally, Callahan works in three dimensions. Her installations evoke a Victorian-era predilection for whimsy. One has the impression of being in a dream world anchored in the 19th century. Eclectic objects, found or meticulously fashioned by Callahan, fill museum space in the cluttered way Victoriana filled rooms of their era. The cabinets which enclose many of her dream “specimens” were constructed by Callahan herself, showcasing her high level of craftsmanship.

Her installation features images from the dreams of eight people. Some, like Darwin’s contemporary Alfred Russell Wallace, are historic figures; others are products of Callahan’s imagination. The “artifacts” in the exhibit have been “surreptitiously plucked” from the dreams of each subject.

One “artifact” from the stenographer’s dream is a mechanized shorthand device featuring many curious bells and whistles, one of which is a glass aperture containing a 19th-century engraving of a pin nib game whose purpose is to project spitballs. Another, tucked into the side of this whimsical machine, is a box containing a miniature brush whose paper-thin bristles are made from a shorthand dictionary—a handy gadget for “brushing up” on one’s shorthand skills.

As dreams are often products of stress, the “artifacts” or “specimens” created by Callahan emerge from stressful experiences of each dreamer. For instance, Wallace spent four years collecting specimens in the Amazon only to have the majority of them destroyed on his return trip, when the boat on which he was sailing caught fire. Numerous “specimens”—lush and surreal and salvaged only in Wallace’s dreams—fill an entire gallery space.

The “specimens” from Wallace’s dream, in particular, hark back to Renaissance painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo, whose work anticipated surrealism. His paintings, like Callahan’s, combine random subjects (fruits, vegetables, sea creatures and library books), radically deviating from traditional art. Nevertheless, Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II so greatly appreciated Arcimboldo’s art that he displayed it in his prized Kunstkammer, his “cabinet of curiosities.” We were not around to see Maximilian II’s 16th-century cabinet, but the Fenimore’s current “Cabinet of Curious Matters” is not to be missed.

The Fenimore Art Museum is currently open Tuesday through Sunday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. through December 31. Closed Thanksgiving and Christmas Day. Info at fenimoreartmuseum.org.