Hatred of Asians isn’t

new, but support helps

Editor’s Note: In honor of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, we asked some of the speakers at the recent rally against violence against people of Asian descent to submit their speeches as columns. The first one submitted came from Bassett researchers and League of Women Voters Co-President Liane Hirabayashi.

Thank you Olivia, and Cate, Riley, Elizabeth, Jaina, Maya and Charlotte for organizing this event.

Today we have the actions of these students and the words of our leaders read earlier as shining examples of how to respond to hate and racism. I’m going to take a few minutes to talk about a different kind of proclamation, the actions that followed, and the consequences of those words and actions.

In 1942, my father Edward was 19, not much older than these students, when he and his family joined 120,000 persons of Japanese descent—more than 72,000 of them American citizens—in being taken away from their homes on the West Coast and incarcerated in hastily built concentration camps—the term used by the US government. This was the ultimate result of Executive Order 9066, issued on February 19, 1942.

Dad’s brother James was 16, sister Esther was 13, and youngest brother Richard was 11. Can you imagine that? All born in the United States, never been anywhere outside Washington State, where their parents were farmers.

They lost their rights as citizens, in fact, they lost the title of “citizen”— instead they were referred to as “non-aliens.”

Words matter, don’t they? From double-speak words like non-alien comes the justification for preemptively locking up a community because, well, they didn’t have the time to figure out who was loyal and who wasn’t. And yet, they did know.

The FBI had been monitoring the West Coast Japanese-American community long before Pearl Harbor.

They had issued a report that the majority of community members were loyal to the US; the report identified the small number who were disloyal and they were arrested.

What happened to that report? Buried. Suppressed. Why? Because the animosity against Japanese immigrants was incredibly high before Pearl Harbor—manifesting itself in the form of laws preventing them from becoming citizens, from owning land, and much more. And the government bowed to pressure and hysteria, and took away their freedom.

All from this fear of what is different. Which turns to suspicion and hatred. And into more words and actions. “Japs go home” say the signs on businesses in 1942. This is my home, says my father, as he and his family pack up only what they can carry. They lost their home, their livelihood, their privacy, their dignity. Because of their ancestry. Because of their race.

And this institutional racism didn’t start with the Japanese. It’s happened to every immigrant population that has come to the US seeking a better life: the Chinese, Filipinos, Irish, Italians, Mexicans, on and on, not to mention the Africans brought here by force and enslaved and the Native Americans forced out of their land. To put it mildly, we have a history of pushing people around.

So let’s talk about some pushback.

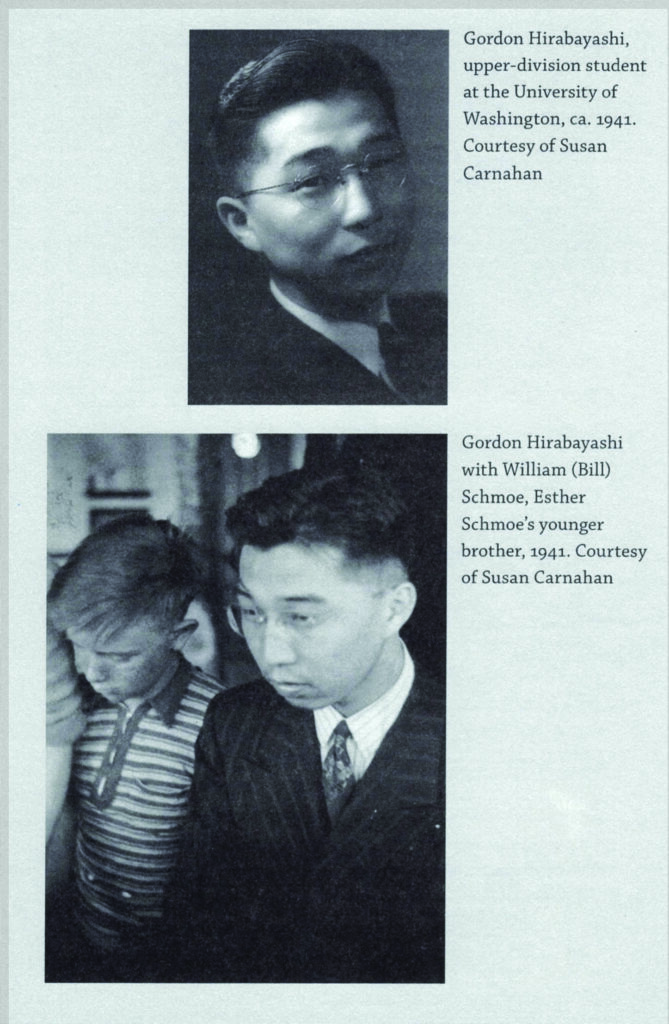

My dad’s older brother Gordon was in grad school at University of Washington in Seattle, when the evacuation orders came down in February 1942. He was 24—about the same age as Olivia’s older brother.

Well, Gordon looked at the word non-alien, and he said, “That’s not me.” On May 13, 1942, almost 79 years ago to this day, Gordon wrote in a statement he handed to the FBI when he turned himself in: “I consider it my duty to maintain the democratic standards for which this nation lives. Therefore, I must refuse this order for evacuation.” Words and actions.

Gordon, Minoru Yasui in Oregon, and Fred Korematsu in California became three test cases against the constitutionality of the wartime orders. All three cases went to the U.S. Supreme Court. All three lost.

My uncle spent the war in prison, serving his time for violating the wartime orders and then as a conscientious objector, following his principles as a Quaker.

From the little you’ve heard today, you won’t be surprised that Gordon never stopped believing that his stand was just.

And when the suppressed FBI report was found in the 1980s, leading to a successful appeal of his case and to his convictions being vacated, here’s what Gordon said: “I did not regret my wartime

decision to stand for my rights. In my own appraisal of the meaning of citizenship in our Constitution the only realistic position available to me was an idealistic one. Anything else would have been the destruction of my self-respect, my values, my beliefs—the necessary ingredients that make up a good citizen.”

So I say to you, be a good citizen and stand up for what you believe in. In the face of manifest injustice, silence is compliance. My friends and neighbors, let your voice be heard, and lead you to act side by side with these students who, with this rally, have made their ideals a reality.

Thank you.