Man Of The World

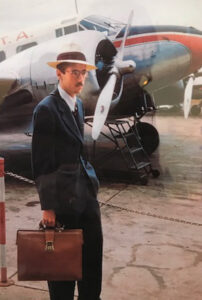

Hugh MacDougall Encountered Adventures Worldwide

By HUGH MacDOUGALL • Special to www.AllOTSEGO.com

Editor’s Note: Hugh MacDougall, one of Cooperstown’s foremost citizens, spent 28 years in our nation’s diplomat corps. On May 15,2020, he recounted several of his overseas’ adventures in a lecture at The Thanksgiving Home, where he resided from April 2019 until his passing on Saturday, March 6, 2021.

In 1958, I joined the United States Foreign Service, where I spent the next 28 years, mostly as a political reporting officer. I served in seven countries overseas, as well as at the State Department in Washington.

In 1961 I was sent to our Embassy at Conakry, Guinea, in West Africa, first as its consular officer clearing American shipments through local customs, and then as a Political officer.

Guinea had broken from France in 1959, and aligned itself with the Soviet bloc. So my little 1961 Volkswagen Beetle was a familiar sight in the Port Area, which was a regular stopping place for Soviet ships returning from Cuba, before and during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.

Thus one day another Embassy officer loaded a Geiger counter in my back seat, covered it with a blanket, and we gradually approached a Soviet ship that had arrived during the night. As we did so, the Geiger counter started to click wildly – and we knew that the Soviet ship was indeed carrying some of the nuclear warheads being returned from Cuba.

For my service in Guinea I was awarded the State Department’s Silver Honor Medal stressing, in part, “his rapport and relationship of confidence with his counterpart Guinean officials.”

My next post was at Recife, a Consulate-General on the northeast coast of Brazil, covering a half-dozen of Brazil’s least known but most interesting states, where I was assigned as political officer.

Shortly after my arrival in 1964, a bloodless military coup took over Brazil – ousting the left-wing Brazilian President Jango Goulart. Only much later did I learn that it had been backed by the American government.

(After a stint in Washington D.C. and studying Africa at the Sorbonne, Paris) I flew in 1968 to Abidjan, the capital of the Ivory Coast – a former French colony which was still closely tied to the French Government.

My prediction that it was headed for a civil war raised very little interest in Washington, though it proved correct in 2002. But it was a very good place to buy African art.

In 1970 I was assigned to the Office of Economic Opportunity in New York City. Most importantly, however, I found that Eleanore Ellsworth of Cooperstown, whom I had known since childhood, was living a few blocks away from me.

On Dec. 26, 1970, we were married by Father French of Cooperstown’s Christ Episcopal Church. Our marriage was a happy one, and lasted almost 44 years until her death in 2015.

Early in 1971, after a brief honeymoon in southern France and northern Italy, Eleanore and I arrived at Lourenço Marques (now called Maputo) which was the capital of the then Portuguese

Colony of Mozambique in southeast Africa, but one fighting guerillas in its north.

I made a point of getting to know Africans, and was rewarded with a second Silver Medal of Honor for, in part: “…sustained and outstanding performance…in advancing the policy and program objectives of the United States…during a period of complex and strained relations.”

From Mozambique, Eleanore and I moved north to Tanzania in 1973, where I was assigned as counselor for political affairs at our Embassy in Dar-es-Salaam.

Here in 1975 I became closely involved in the release of three Stanford University students and a Dutch nurse, working at Jane Goodall’s Chimpanzee research station at Gombe on

the shore of Lake Tanganyika. In the middle of the night of May 21, they were kidnapped by a boat from the Zaire side of the narrow lake.

It was some weeks before one of the students was released – with a long list of demands – by a guerilla group led by Laurent Kabila, then in revolt against the Zairian government of Mobuto.

A few weeks later an African named General Nondo appeared at our Embassy and offered to negotiate. Secretary of State Kissinger had prohibited any negotiations with so-called terrorists,

but our ambassador – an African-American – rejected this on the grounds that this event was not likely to spread anywhere else. General Nondo spoke only French and Swahili, so I was placed in charge of him until we could ascertain the views of the Tanzanian Government.

Eventually a committee was formed, including the American and Dutch Ambassadors, representatives of the Tanzanian government and of Stanford University, and a few others including myself.

The kidnappers’ demands were eventually reduced to something like 200,000 British pounds in cash.

To cut a long story short, the money arrived (I do not know from where) and I helped General Nondo count it out. He returned home with it, and shortly afterwards the remaining three hostages were released and the crisis was ended.

For this I received a Bronze Honor Medal from the Ambassador, reading in part: “For exemplary service, outstanding loyalty, and selfless devotion to duty under adverse and trying circumstances.

For contributing personal effort and initiative leading to the safe release of three American and one Dutch kidnapped students during the period May-July 1975.” I also received a similar medal for my overall performance in Tanzania.

My last overseas post was in Rangoon, Burma (now Yangon, Myanmar), as counselor of embassy for political and economic affairs, where I served from 1981 to 1984. Since 1961, Burma had been a military dictatorship in which Army Officers ran both the government and most economic organizations. Except for foreign diplomats and representatives of International Agencies, foreigners were limited to small numbers of tourists.

Burma was a fascinating country, with a culture still largely unchanged from pre-colonial times. It has hundreds of Buddhist temples, including the world-famous ancient city of Pagan. As diplomats we were able to travel more than tourists and to appreciate much of Burmese traditional culture. In that sense, it was perhaps my favorite of the seven or so countries in which I served.

Oct. 9, 1983, was a Sunday, and I was at home in Rangoon, but happened to be in charge of the Embassy. Our ambassador had left the post in September, and her successor had not yet arrived. Our deputy chief of mission was traveling upcountry.

The president of South Korea, Chun Doo-hwan, was in the midst of an official visit to Burma, along with many officials from his government; Eleanore and I had represented the United States in welcoming his arrival at the airport.

On that Sunday, as was standard practice, the South Korean president was scheduled to lay a wreath at the Martyr’s Mausoleum, outside the city, honoring Aung San, the founder of Independent Burma in 1947, and an event to which only South Koreans and a few Burmese officials were invited.

Suddenly I heard a large explosion. Three North Koreans had been landed by submarine with orders to assassinate the South Korean president as he laid the wreath, by setting off from a distance three bombs that they had secreted at the mausoleum.

I quickly checked with the hotel where the South Korean delegation was staying, and learned, that while much of the delegation was already at the Mausoleum, President Chun Doo-hwan had been delayed by conversations with the Burmese Government.

Knowing that the President’s arrival was delayed, the Burmese national band had decided to practice the South Korean national anthem one more time. The North Koreans, hiding in the hills above the mausoleum, assumed that the President had arrived, and set off their three bombs—only one of which detonated.

Nevertheless, 17 high-ranking South Korean officials were killed, including the Foreign Minister and three other major Cabinet officials, as well as four Burmese. Among the killed was the South Korean ambassador to Burma, whom I knew very well;

46 people were wounded, many of them severely.

The South Korean President, who had escaped the bombing by chance, cancelled his Asian trip and returned immediately to Seoul. From the American point of view, a major concern was that the bombing might lead to war between the two Koreas. As soon as the basic facts were known, I sent to Washington the only message of my career

of a classification that would ensure that our President would be immediately awakened and informed.

Meanwhile, what about the many wounded? Through our military attaches we contacted the American Embassy in the Philippines and arranged for a medical plane to be sent immediately to Rangoon to treat them, and to transport the most seriously injured to hospitals in the Philippines.

Of the three North Koreans, one was shot while being captured, the other two were placed on trial. I attended some of the sessions. Of these, one who refused to talk was hanged. The other, who talked freely, was sentenced to life imprisonment and died in a Burmese prison in 2008.

That was, perhaps, the most exciting event in my overseas diplomatic career. I returned to America on the 5th of July, 1984, and spent two years in charge of the training of mid-level political officers in Washington.

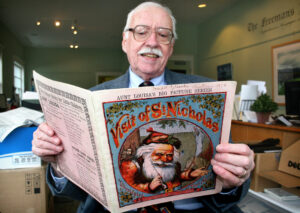

MacDougall shared an early printing of “Visit of St. Nicholas” during the 2006 Christmas season.

In 1986, I retired from the Foreign Service after 28 years, and Eleanore and I returned to Cooperstown. Her mother was still living at home, with live-in help, at 8 Lake St., and we rented a small house at 32 Elm St.. Eleanore resumed her previous occupation as a teacher of piano, as well as organist at the Baptist Church … I quickly decided to devote the rest of my life to Cooperstown, and to its world-famous author James Fenimore Cooper.