Indiana Remembers

Tiny Greenville Erects 1st Marker

To USDA Chief, Richfield Native

By JIM KEVLIN • Special to www.AllOTSEGO.com

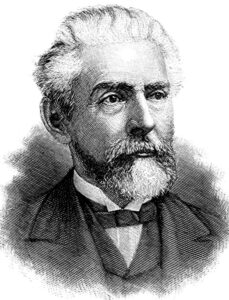

RICHFIELD SPRINGS – From 655 miles away, Greenville, Ind., is claiming Norman Jay Colman, the nation’s first U.S. secretary of agriculture, born on May 16, 1827, in Richfield Springs, as its own.

“We wanted to honor him: He was the first to hold a national office,” said Matt Uhl, chairman of the Greenville Historic Preservation Commission, which is planning to unveil a historic marker on Sunday, Nov. 1, in front of the Greenville Elementary School. “As historians, we have a responsibility and interest in telling stories like his.”

A town of only 900, Greenville can boast connections to two national figures: John B. Ford, whose early local experiments with plate glass grew into Pittsburgh Plate Glass, now Fortune 500 PPG Industries, and Colman.

According to Uhl, 41, a banker with Farm Credit Mid-America, this could be the first memorial to the early promoter of Agricultural Field Stations, son of Hamilton and Nancy Coleman, who was born on May 16, 1827. There are 10 historical markers in the Town of Richfield, but none honoring Colman.

Uhl was assisted in researching and obtaining the marker by Andy Lemon, 39, a Greenville Town Board member and a fellow member of the Historic Preservation Commission board. “He was really passionate about this,” said Uhl.

While information on Norman’s early days in northern Otsego County is scant, his father was quite prominent, serving as county commissioner of deeds in 1838 and as Richfield town supervisor in the late 1850s, according to “Six Generations in Otsego: The Colman Family History,” published in 2018 by Sara Campbell.

Given his family’s standing and the westward migration of the period, it’s understandable that by age 23 young Norman had the education and means to find himself in St. Louis, Mo., studying law.

In 1850, law degree in hand, Colman was hired as the first principal of Greenville’s brand new Floyd County Seminary, “a new, spacious brick edifice, containing two distinct departments, and capable of accommodating upwards of 150 students,” according to a newspaper ad over Colman’s signature. Tuition was $4-8 a year for in-county students.

In its first year, the seminary grew from 40 to 100 students, according a blog posting Uhl developed to make Colman’s story available. By January 1851, the New Albany (Ind.) Daily Ledger reported on exercises the two-room brick schoolhouse and remarked on “intelligence displayed by the pupils.”

At the time, seminaries like Floyd County’s were built by local subscription from parents looking to provide opportunities to their children. But in 1852, the Indiana Legislature created a public school system, absorbing institutions like the Floyd seminary.

Perhaps seeing the handwriting on the wall, by then Colman had returned to St. Louis to open a law office with a fellow St. Louis Law alumnus, Michael Kerr. He took his new bride, Clara Porter, daughter of the Porter Public House proprietor, with him. (Their daughter, Laura Kate, would eventually marry a governor of Maine.)

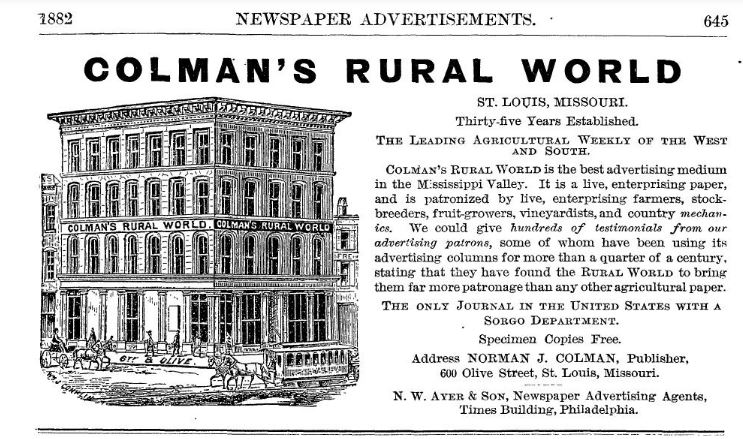

In St. Louis, he was elected Fifth Ward alderman, and in 1855 founded his first newspaper, The Valley Farmer, dedicated to sharing best farming practices with the region’s growing farming community. (Uhl reports that, as a boy in Otsego County, he avidly read The Albany Cultivator, which kept farmers apprised of “tips, tricks” and the latest farming products.)

During the Civil War, Colman served in the 85th Missouri Militia. Returning home, he renamed the newspaper Colman’s Rural World, and expanded distribution up and down the Mississippi.

In 1862, during the Civil War, Vermont Congressman Justin Morrill and University of Illinois professor John B. Turner championed the Land-Grant College Act, signed by President Lincoln, that endowed colleges (like Cornell, locally) to develop and pioneer better farming techniques.

“One can easily draw the connection and passion Colman had with empowering farmers with better, empirical information to increase agricultural yields,” Uhl writes.

Championing the movement raised the influence of Colman’s Rural World throughout the decade, with the boy from Richfield Springs rising to president of the Missouri State Board of Agriculture. In 1874, he was elected lieutenant governor.

In April 1885, newly elected President Grover Cleveland brought Colman to Washington D.C. as U.S. commissioner of agriculture. In February 1889, sensitive to farmers’ growing clout, Cleveland elevated the commission to a cabinet-level department, and Colman was likewise elevated to first USDA commissioner.

By then, Democrat Cleveland was a lame duck, having lost to Republican Benjamin Harrison, departing in March, and Colman – having served just three weeks – left with him.

Colman returned to St. Louis, and resumed editorship of the Rural World until his death at age 84 on Nov. 3, 1911, from pneumonia. He is buried in St. Louis’ Bellefontaine Cemetery.

The Greenville commission’s first goal was to obtain a state historic marker for Colman, but Indiana’s Division of Historic Preservation & Archeology found his in-state role was too narrow, and encouraged Uhl and Lemon to raise funds for a local marker that was a replica of the statewide one.

That will be unveiled on the first Sunday in November to the accolades of students, officials and an approving citizenry, Uhl said.

(Note: This narrative was put together from Uhl’s blog post, Wikipedia, the USDA website and other sources. In Richfield accounts, the name is spelled “Coleman,” with an “e”, and there are many county families that spell their name that way. After moving to the Midwest, Colman spelled his name without an “e.” His newspaper was called Colman’s Rural World.)