Column by Adrian Kuzminski, September 7, 2018

THE GOAL: ECONOMIC, POLITICAL FREEDOM

Populism As American As Apple Pie

Ever since the last presidential election the words “populist” and “populism” have been widely bandied about, mostly as pejorative terms.

Ever since the last presidential election the words “populist” and “populism” have been widely bandied about, mostly as pejorative terms.

A populist politician, we often hear, is a demagogue who wins votes by inflaming the resentments and emotions of ordinary people at the expense of rational thought. Those who fall prey to populism are no more to be trusted, critics suggest, than the politicians said to manipulate them.

It’s a curious feature of populism that it defies the normal left-right political spectrum. These days we have left-wing and right-wing populists.

In the last election, Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump were both called populists. And historically, we’ve had left-wing populists like

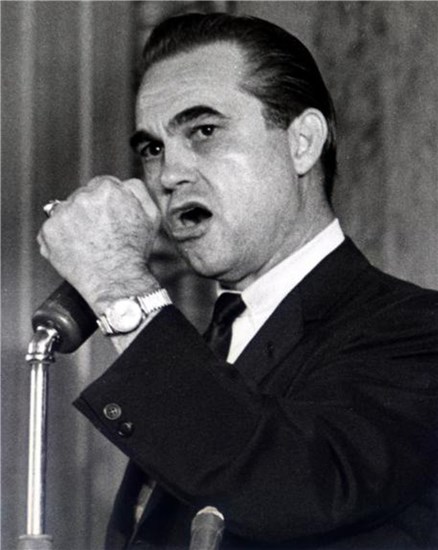

Huey Long, and right-wing populists like George Wallace.

It is the corrupt elites, populists argue, who are to blame for the insecurities and troubles of the middle-class. If you’ve lost your job, are over your head in debt, can’t pay your bills, don’t have adequate health care, lack a decent pension and feel that your values are being undermined, populists say, it’s because of them.

The elitist agenda, they say, is what drives inequality, including the outsourcing of jobs, corporate globalization, union-busting, deregulation and the machinations of the deep state. All this, in their view, represents the tyranny of the one percent, not the welfare of the 99 percent.

It doesn’t require a demagogue to convince people that these are real problems, not paranoid fears. The trouble with modern left- and right-wing demagogues is their unwillingness or inability to get at the root of the problems which they try to leverage for votes.

It’s telling that politicians accused of populism today don’t call themselves populists, as well they shouldn’t. They’re faux-populists who

stop short of challenging the status quo of continuing inequality.

Some history might be useful here. It’s largely forgotten that there was a vibrant populist movement in 19th century America. It was represented first by the Farmers Alliance after the Civil War, and then by the People’s party in the 1890s.

The People’s Party candidate for president in 1892, James B. Weaver, got over a million votes and carried four states. Over 40 populists were elected to Congress in the 1890s, including six United States senators, along with numerous governors and mayors.

Today such a populist wave would be totally shocking, which is a measure of how narrow our political options have become.

The classic 19th century American populists were the last serious political movement in this country to defy the duopoly of the two major parties and lock-step left-right thinking.

Their defeat in the 1890s by their better-funded and organized opponents ensured that the issues they tried to raise would henceforth be excluded from national political debate – as indeed they have been down to the present day.

What were those issues? Classic populists – unlike their modern faux-populist successors – rejected the two options that even then defined American political discourse: corporate capitalism and state socialism.

Corporate capitalism consolidates economic and political power into giant top-down structures controlled by a handful of rich investors and executives. State socialism consolidates economic and political power into giant top-down structures controlled by a handful of politicians and bureaucrats. You see the similarity.

Classic populists rejected both socialism and capitalism as tyrannical absolutist ideologies. Instead they tried to balance the need for collective action with individual freedom.

They sought to maximize equality by making sure that private property was widely distributed, and that concentrations of economic power were highly regulated, if not eliminated.

They were advocates of small, independent producers: farmers, artisans, fabricators and generally owners of moderate-scale, local, independent enterprises.

They aimed to relocalize democratic government in the decentralized Jeffersonian tradition of home rule. You can have genuine free markets and real democracy, they argued, only when citizens enjoy individual economic security as independent owners of productive property, and can practice meaningful local democracy.

Classical populists weren’t led by demagogues – who flourish in modern, impersonal, mass politics – but by a variety of grassroots activists (as we would say today) who focused on the issues then crucial to economic and political independence, especially the regulation and decentralization of corporate power (especially in government, finance, transportation, and communications).

They advocated public banking as a way of redistributing capital to individuals and small businesses by allowing easy public access to credit at low interest rates.

(More about populism can be found in my book, “Fixing the System: A History of Populism Ancient & Modern,”available at amazon.com.)

The politicians who try to exploit populist concerns today aren’t really populists. They’re usually left-wing state socialists (Bernie Sanders) or right-wing corporate capitalists (Donald Trump).

They advocate more big socialism or more big capitalism to solve our problems. But neither socialism nor capitalism is likely to produce the kind of individual economic and political freedom the original populists envisioned.

The problems they raised are with us more than ever. Maybe it’s time to take their solutions seriously.

Adrian Kuzminski, retired Hartwick College philosophy professor and Sustainable Otsego moderator, lives in Fly Creek.