THE NIGHTINGALE & THE FIREFLY/PART III

In Ninash, Love Lives

Editor’s Note: This is the third article in a three-part series on Ashok Malhotra, who retired in December after almost a half-century in SUNY Oneonta’s Philosophy Department. In was published in Hometown Oneonta & The Freeman’s Journal on March 10-11, 2016.

By JIM KEVLIN • for www.AllOTSEGO.com

ONEONTA – On Aug. 28, 1967, Ashok Malhotra completed his journey from the Sutlej to the Susquehanna, arriving in Oneonta, 6,952 miles away from his native Ferozepur, on one of those brilliant late-summer days, little knowing it would still be his home almost a half-century later.

“All the stores were on Main Street” – Bresee’s, Sears, J.C. Penney,” he recalled. Downtown was both retail and business hub. “People were walking – and dressed so nicely.”

It was long before the Clarion Hotel rose, so he and wife Nina – her parents had driven them up from New York City – could look down busy Broad Street, lined with restaurants and bars past the depot (now Stella Luna) and see the view that inspired “City of the Hills.”

A few weeks before, he having finished his course work on his philosophy doctorate at the University of Hawaii, the newlyweds had been working their way through that list of colleges that used to appear in the back of Webster’s Dictionary, sending out cover letters and resumes, looking for the husband’s first break.

Eighty replies – no luck – when the letter arrived in Honolulu from the State University College of Education at Oneonta. “You are on our priority list,” wrote then-dean Carey Brush, who was one of “The Trinity” – Ashok would learn – along with President Royal Netzger and Vice President (and future president) Clifford Craven.

One morning, the phone rang at 7 a.m. – noon Oneonta time – and Nina summoned her sleepy husband. It was Winfield Nagle, University of Hawaii Philosophy Department chair. Brush had just called Nagle, who reported: He’s calling back at 8. “He’s going to offer you a job.”

At 8 the phone rang. “Can you start a philosophy department?” Brush asked. Don’t you need to meet me? No, said Brush, he’d spoken to Nagle: “You’re the best student he ever had.”

•

With $500 to their name, the couple took a room at the old Oneonta Hotel – “the strangest, darkest place I ever lived” – and, no car, began looking for an apartment.

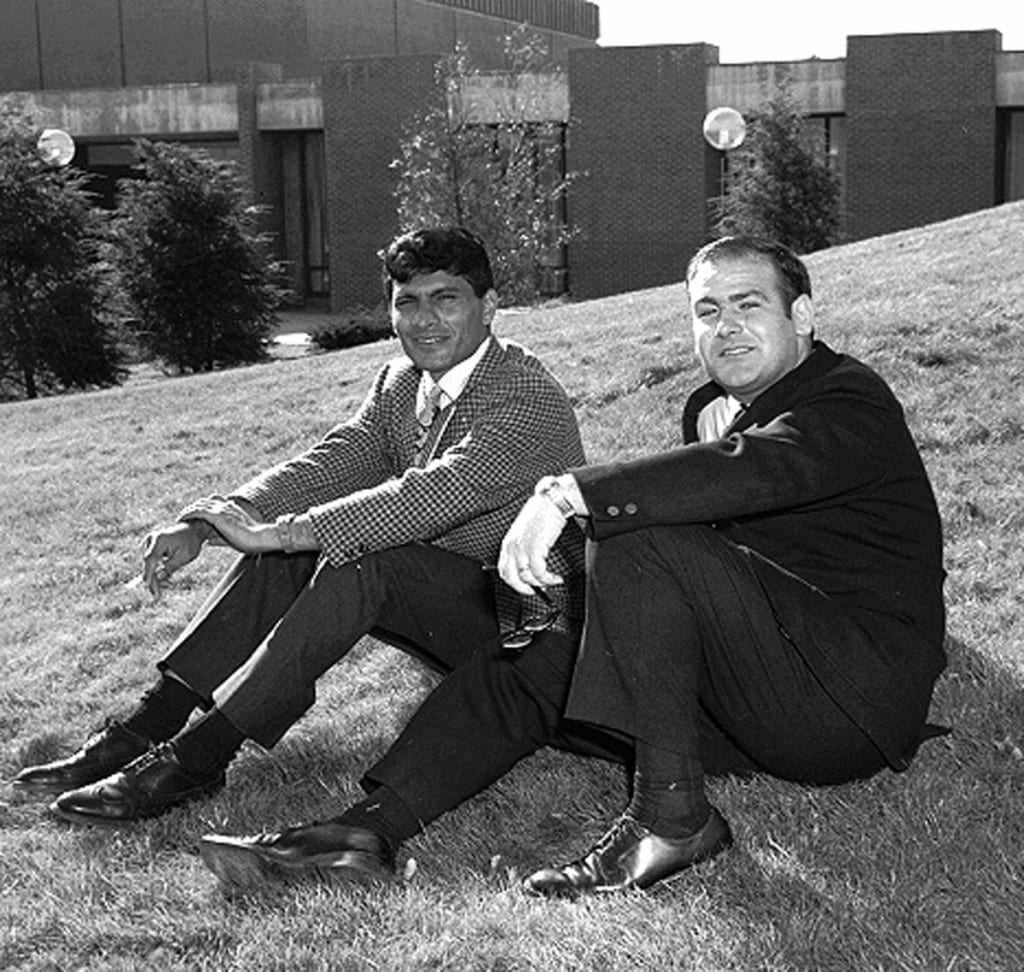

Malhotra went up to a campus in the midst of Rockefeller-era construction – only a half-dozen of today’s 50 buildings were complete, met The Trinity, and was introduced to Anthony Roda, his Philosophy Department co-founder. Roda (he passed away in 2010) was 28; Malhotra, 26.

The first couple of years, their department was in a trailer set between Morris and Alumni halls in what today is a parking lot. There were two offices, each “double the size of an airplane bathroom,” and a classroom.

Brush was acting chair. “He was gung-ho on making SUNY Oneonta” – a teacher-training school – “into a liberal arts college. He knew the core of any liberal arts college was the Philosophy Department.”

Creating the department would require approval of the Faculty Senate. Brush cautioned, “It’s going to be a tough sell job. Be nice; be patient.”

The snack bar in Fitzelle “became the hub” of a campaign of “Indo-Italian cooperation,” Malhotra related. Roda approached biology and chemistry professors, engaging them in discussions about the philosophy of science. Malhotra did the same with literature.

Meanwhile, in the first two years, Malhotra and Roda taught 22 courses, 11 each. ABDs (Ph.D.s with “all but dissertations”), the young men spent 16 hours on weekends in the Milne Library, writing their theses; and both the Malhotras and Rodas had their first children.

Each Friday, they’d debrief at the Rizzo brothers’ Molinari’s – Tony introduced Ashok to anchovies – and they began looking ahead, imagining what philosophers would need to know to navigate the 21st century. India and China would have the largest population, they reasoned, and thus were “the most prominent countries whose philosophy we must know.” In retrospect, Malhotra realizes he and Roda had anticipated “global connectedness” by three decades.

In those days of The Beatles’ Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and Ravi Shankar, that decision was a big hit, and the department, approved by the Faculty Senate and expanded to four teachers, was instructing 1,200 students. “People were thirsting for it,” said Ashok. “Students flocked to these classes. They were packed, packed.”

Three years in, both Roda and Malhotra had tenure and were promoted from assistant to associate professors. In 1970, Ashok took Nina to India for the first time: “She loved my family,” he remembers, and, “immediately, my family” – his mother, and his 10 brothers and sisters, and many nieces and nephews – “fell in love with her – an exotic beauty from the West.” The four dozen relatives were a revelation to the only child from New York City’s Stuyvesant Town.

•

And as the 1970s went forward, a long-held ambition took hold, “to go back to India, to help the people of India,” Malhotra said.

At the time, the fabled Peter Macris, a pal of Ashok’s, was taking students to Wurzburg, Germany; Dan Larkin, the future provost, to Ireland; Alexander Yunah, to Israel. “In three weeks, they’ll come back, burning with ideas,” Malhotra pitched to Ellen Caswell, then director of International Studies.

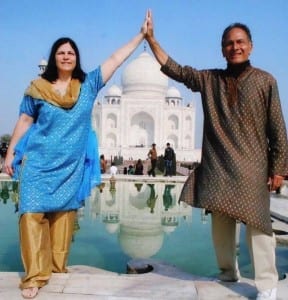

Launched in the 1979-80 school year, 20 spots for a three-week excursion to India were “filled instantly.” Malhotra took Nina and their two sons, Raj and Ravi, with him, on an excursion that mixed lectures with on-site visits, to the Taj Mahal, the Red Fort, the Pink City and other fabled locales.

In 1985-86, the three-week program was expanded to a semester. And in 1996, “Learn and Serve in India” began, the result of life-changing tragedy.

Everything was fine. By 1986, Nina, then 43, a dedicated teacher, had obtained a master’s in counseling. Ravi was 14, and Raj was at Hobart, en route to law school at NYU.

•

One day, the husband came home to find his wife in tears. During a routine check-up, she had been diagnosed with Stage 4 breast cancer. “That was shocking news,” Ashok recalled. “She was never sick.”

The next day, he drove up to Cooperstown to confer with the doctor face to face. In those days, Stage 4 patients lasted six months, he learned; only one in 500 survived five years. “Doctor,” the husband said, “she will be the one.”

Back in their Center Street home, the couple talked. “Suppose we live for 30 years; what would we want to do?” he asked. “Let’s create a list. Tell me 10 things you would like to do.”

And so they began. One, travel: Bali, Prague. “I will be your firefly,” he said, “showing you the world.”

Two, she said: “I would love to listen to Mozart every day.” Three, help the family in India – to come to the U.S., if they wish. (Eventually, Ashok’s mother, Vidya, joined her son and daughter-in-law, amazed by their Center Street home’s kitchen, which she quickly adapted for Indian specialties. She lived until age 92.)

Four, eat in the 100 best restaurants. Five, renovate the house; add a Jacuzzi. Six, plant flowers. Seven, yoga and meditation daily … and so to 10.

Keeping the news within the family, “we started doing that,” Ashok said, adding, “Every year, she was able to get rid of the cancer; every year, it came back.”

“Five months before she died, she said, ‘Ashok, we have done the 10 things’,” he recalled. Only one regret remained: “You will forget me.”

“Nina,” he replied, “I will never forget you.”

And so they discussed the concept of the Ninash Foundation – the name combines the wife and husband’s names, and it combined their mutual interests – teaching, and helping his homeland. “A month later” – Dec. 27, 1991 – “she died,” Ashok said.

Nina wanted to be cremated, and her ashes to be scattered in the Ganges, the Hudson and the Susquehanna. “And we did that,” the husband said.

Both boys were gone, although Ravi would finish up at SUNY Oneonta after two years at Geneseo. The father was despondent, negative, alone.

•

On Valentine’s Day, 1992, he emerged from an evening class into a snow storm. Sitting in his car, he said to himself, “I can’t go on. But I must go on. Only the living carry the memory of the dead.”

He turned the ignition and the panel on the automatic shift lit up. N – the car was in neutral; so was the driver. He observed R; reverse. And then D – there is no option, he said to himself, but to drive forward. “The gearshift of my life is in my own hands,” he said to himself.

So he began to work on the common dream, the Ninash Foundation. Son Raj was in law school, so he drew up the legal papers. Ashok and Nina had owned the home next to their own as a rental property; he sold it and used the proceeds as seed money.

SUNY Oneonta Education Professor Suzanne Miller signed on as his co-director. T-shirts and pizza sales by his dedicated assistant, Josie Basile, help supplement revenues, and soon donations and grants followed.

He began the Yoga & Meditation Society at SUNY Oneonta, teaching methods that had helped him and Nina keep worry at bay during their final years together.

After concluding he and his students had been approaching the semester abroad “as colonialists,” observing but not become part of India, he transformed the semester abroad into “Learn and Serve,” which included study, visits to historic sites, but also service to the Indian people.

He also promised himself, “I will fall in love again.” And five years later he did, marrying Linda Drake, director of SUNY’s Center for Social Responsibility & Community, a partner in the Ninash ventures.

Meanwhile, the foundation embarked on its first venture, an “Indo-International Culture School” in Dunlod, which a “Learn and Serve” group from SUNY launched in 1996 for 50 students, girls and members of the “untouchable” class. Today, expanded to include high school, it is educating 630 students.

When she was Oneonta mayor in the late 1990s, Kim Muller established a sister-city relationship with Dunlod, and SUNY then-president Alan Donovan visited there, reading Muller’s proclamation at a ceremony.

Since, additional schools have been founded, including at Kuran in 2001 and Mahapura in 2004.

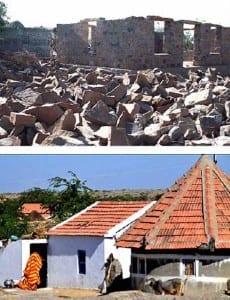

The Kuran school was actually the more modest of two undertakings that came out of the earthquake that struck the state of Gujurat on Jan. 26, 2001, leaving 600,000 homeless.

•

The day the news arrived in the States, Malhotra found 30 e-mails in his inbox asking, What can we do? He arranged an aid trip, and recruited Karen Huxtable, then a TV reporter for WUTV, Utica, now Bassett Healthcare spokesperson, and her camera man, Keith Hunt, to come along.

The TV station agreed that, during the six days Huxtable and Hunt were there, they would end the evening news with a three-minute report, and cap the reportage with an appeal to its American viewers to raise money for the tragedy.

With only a Jeep, granola bars and water, the trio traversed the devastated area. At Kuran, a village of 1,200 people, including 205 children, they found all the homes razed.

How much does it cost to build a home for a family of four? Ashok asked. $500. Ninash immediately pledged $5,000, with the caveat the community needed to solicit NGOs (non-governmental organizations) to build the other 190 homes. Second caveat: get it done in six months.

The only buildings that had survived the earthquake were oval, and so all the new homes were oval. Astonishingly, By June 26, 2001, as agreed, the job was complete.

During the process, Malhotra learned Kuran’s literacy rate was 13 percent. “You need food, water, shelter,” he told the villagers. “You also need education.” And so the Kuran school was founded.

The schools in India have been a continuing source of satisfaction to their benefactor, who has just returned from his latest trip to Dunlod, where the students celebrated their founder’s visit on Dec. 21 with a bonfire.

He was particularly energized by the success of the graduates – two are in medical school, two in business school, others in secretarial school, still others in the Air Force.

While Ashok Malhotra rose from the floods of Ferozepur, struggled through India’s MIT, won the nationwide scholarship that brought him to the East-West Center, fell in love with his Nina, rose to Distinguished Teaching Professor of Philosophy in the SUNY system, and was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize every year since 2010, the cycle of life continued in his homeland.

His grandfather, who inspired him and insisted he receive an education, lived until 1990. At the time, his grandson, at college student, returned to Ferozepur. The older man had undergone a successful operation, but a too heavy dose of anesthesia had put him in critical condition. The grandson spent the night at his beloved mentor’s bedside, holding his hand. And then he died.

“He was on top of the world,” his grandson remembers. “And he suddenly disappeared. It was a shocking experience.”

As is life, although with less of the drama, the joys and tragedies, related by Ashok Malhotra. “From shoka comes shloka,” he reflects, repeating an Indian proverb. From grief, comes poetry.

Great story of a humble, but great man. As a former student of Dr. Malhotra, I found his story fascinating. Wishing him all the best in his continuing endeavors to make a difference in this world. Thank you.

Great to hear from you!

Thank you Joy for your very kind words! They are much appreciated.