This Nasty

Little Parasite

Is Meaningful

By JENNIFER HILL

Parasites. That doesn’t sound good.

But SUNY Oneonta biology professor Florian Reyda says having a variety and plentiful parasites “is a sign of a healthy ecosystem, of biodiversity.”

By that measure, Otsego Lake is quite healthy. Especially now that Margaret Doolin, a student in SUNY’s master of science biology program and one of Reyda’s advisees, had discovered a parasitic

species from the lake unknown to the science world.

Her research, under Reyda’s guidance, began as “a starter project” when he gave her an unknown “thorny headed worm” in January 2016 to identify.

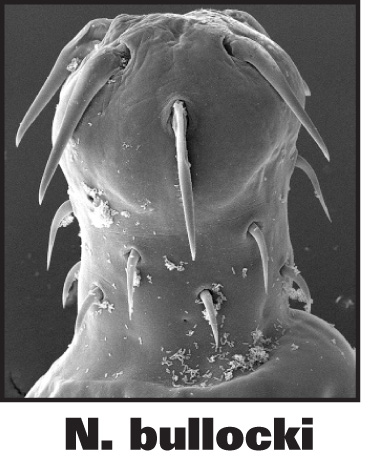

Working with her mentor, Doolin took “many, many measurements” of the “fine internal structures” of the new worm and “morphologically very similar” ones. After discerning discrete differences between them, she and Reyda used DNA evidence to corroborate the morphological evidence.

They found out that, indeed, the thorny headed worm was a different species.

Their work on Doolin’s discovered parasite, named Neoechinorhynchus bullocki was published in the December 2018 issue of the Journal of Parasitology. Doolin is now pursuing a Ph.D. in biology at the University of Utah.

The N. bullocki is unusual in that it only seeks one fish to attach itself to, the White Sucker, a bottom-feeder. While eating, the White Sucker will accidentally ingest N. bullocki eggs that rest on Otsego Lake’s floor.

After the eggs hatch inside the fish, the N. bullocki uses hooks to latch onto the White Sucker’s intestines and takes in digestive matter. The parasite is mouthless; it absorbs the White Sucker’s nutrients through its skin. The eggs exit the fish with its feces and drift to the bottom of lake, and the cycle repeats itself.

N. bullocki’s and other parasites’ life cycles would not make good dinner conversation, but Reyda said they are an important part of the food web. By a “food web,” Reyda means the interactions of different species within an ecosystem. White Suckers and other fish that host parasites are preyed on by fish, such as bass and trout, which are then eaten by birds of prey, such as eagles.

“They go from host to host, adding a whole other dimension to organisms because they move up the food chain,” he said.

Reyda does acknowledge that while the parasites contribute to Lake Otsego’s health, they are not benign. “Although they don’t kill their hosts – because they would die, too — by definition, parasites damage the host,” he said. “So, they aren’t healthy for the hosts.”